Net neutrality. A bland phrase capable of sparking a digital revolt.

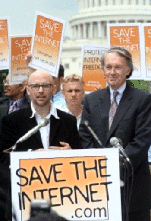

In the United States it's the hot-button Internet issue of the day, a threat deemed so grave to free expression it gave rise to a stunning right-left coalition and galvanized celebrities and rock icons like REM with church groups, rights groups, academics, the CEOs of Google and Amazon, web pioneers Vint Cerf and Tim Berners-Lee and the 1.5 million Americans who sent a petition to Congress. (Not to mention providing the raison d'être for this hip short film primer on the topic.)

In Canada, on the other hand, the latest count on Kevin McArthur's online net neutrality petition clocks in at, well, a paltry 217 signatures.

It's not that the fight over net neutrality doesn't matter in Canada. At issue here, as in the United States, is whether telecom companies can favour some Internet sites over others by charging different rates to different customers and making some sites much easier to access than others. Critics say the practice threatens the Internet's level playing field and would stifle smaller independent voices on the web.

At stake is nothing less than democratic speech in the Canadian modern era, says McArthur. "I mean this is The People vs. Larry Flint all over again, only this time it's digital."

Odd then that public debate on the issue in Canada has been a non-starter. Especially when, between the two countries, it's Canada where the World Wide Web is most poised to become the latest plaything of the rich and the powerful.

'Sounds innocuous, but isn't'

To understand what net neutrality is and why it's important, it pays to take a look at what's been happening south of the border.

In 2005, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) redefined "broadband," recasting it as an information, rather than a telecommunication, service.

"It sounds like an innocuous change, but it isn't," explains Ben Scott, a spokesperson for net neutrality for Free Press, a media democracy NGO based in Washington, D.C. With the stroke of a pen, Scott says the decision undid the entire regulatory regime attached to telecom services, thrusting them into "a category that has virtually no regulations."

The change didn't bode well for a broad spectrum of Internet users, from start-up companies to anyone who uses Google or YouTube. Whereas previously telcos were legally obliged to deliver packets of bits and bytes blindly, as an information service that restriction was no longer in force. This opened the door for what Scott calls a "CEOs-go-to-Wall-Street" scenario: almost immediately, the major carriers began to toy with the idea of creating a two-tier Internet, replete with a fast-track for content creators willing to pay for preferential service, and a slow lane for everyone else.

The idea of telcos acting as gatekeepers, combined with what that would potentially and physically do to the Internet, set off a firestorm of public protest. And in spite of the fact the telcos spent hundreds of millions of dollars lobbying Capitol Hill, a bill that would have paved the way for a two-tiered net died along with Republican majorities in the House and the Senate.

Now, Scott says a climate of intense public and congressional scrutiny will bar the telcos from acting as gatekeepers until net neutrality can be protected by law.

But what's to stop them in Canada? Less and less, it would appear.

Canada's hands-off stance

Professor Michael Geist has been talking about net neutrality and digital rights in his Toronto Star and Ottawa Citizen columns and via his blog for a while now. The Canada Research Chair of Internet and E-commerce Law says that even though Canada is rapidly deregulating the telecom industry, public debate amounts to little more than a whisper.

Just like in the States, net neutrality in Canada hovers in a state of legal limbo; the threadbare language of the Telecommunications Act means that two-tier Internet is more than a distant possibility; it's already here.

"I think it's already happening now but for the most part people don't recognize it," says Geist, who is based at the University of Ottawa.

"Some of the providers are already engaged in some of these kinds of activities, with little transparency and considerable uncertainty as to whether or not the legal system prohibits it."

Geist offers the example of profs who post their lectures online via an application called BitTorrent, free software designed to send large amounts of multi-media data from point A to point B. He says lately these video clips and audio files "slow to a crawl" when students try to download them because of "package-shaping" practices by companies like Rogers.

Digital profits up for grabs

Packet-shaping, or prioritizing the kinds of information being sent through the pipes, is the thin edge of the wedge, says Geist. All kind of digital rights are up in the air right now.

Much of this is because Internet service providers (ISPs) like Telus and Shaw have always offered "unlimited" bandwidth to subscribers, counting on the fact that the vast majority of users only use a sliver of it.

But with today's wave of user-generated content -- video, wikis, podcasts, MP3s, open source software and Internet telephone -- the old "unlimited" paradigm is broken. Telecoms are as tired of watching the average user eat up more and more bandwidth as they are of watching 100 million video clips a day zip through their wires, via free sites like YouTube. And their shareholders aren't seeing any of that Internet cornucopia -- like Google's recent $1.65 billion purchase of YouTube -- reflected in their company's quarterly reports.

While he says he can appreciate the telcos' concerns -- something's got to be done about the shrinking amount of available bandwidth -- Geist says they're going about it the wrong way.

"If all you're doing is saying, 'This is our existing service and we just want to extract additional dollars because we think Google makes too much money'...I don't know that that's a particularly convincing argument."

McArthur goes further. He says companies are in effect creating a problem so they can charge to fix it. "[Even] if everyone paid for a tier-one service, it would be THE EXACT SAME service we have today," he wrote by e-mail. "Quality of service only works while someone else is getting screwed."

"It's an attempt to extract more rent out of your server," Geist summarizes, "even if it comes at the expense of both their users' interests and the broader interest of the Internet as a whole."

Telus declined to address the issue of net neutrality in an interview and Shaw representatives did not return calls.

COA versus CNN

Steve Anderson's situation brings the potential effect of two-tier Internet into focus. Anderson is a master's student in online media studies at Simon Fraser University. He's also the managing editor of an independent online news source called COAnews, where he and a coterie of mostly volunteer editors stream a lot of audio and video files that sometimes fly in the face of what you see on the evening news. Under a two-tiered system, he says COA's shoestring budget would almost certainly keep it off the fast track.

"Right now we can literally compete with CNN or whatever if we provide news that people want to look at," he explains. "But if that situation goes through, then we just can't afford to pay the fees that CNN can, just like we can't afford to put up a cable news television show."

With few willing to wait for clips if they download at a snail's pace, the slow lane bottle-neck would be the death of independent online media, both for COAnews and for the thousands of other grassroots efforts trying to get their message out there. The Internet, he thinks, is in danger of falling in the for-profit footsteps of its predecessors radio and television.

Telus you didn't do it

Another wrinkle with deregulation is what happens when the carriers start to peep at what it is they're carrying, and then discriminate based on what they see. The landmark example -- the one that even advocates in the U.S. cite -- actually took place here in Canada when Telus blocked a website run by striking Telus employees called "Voices for Change."

Free speech activists were furious, but the company defended itself, saying it was acting to protect the identities of the people who chose to cross the picket lines, whose photographs were purportedly posted on the site. Regardless of their rationale, Telus cut access to another 766 totally unrelated sites by pulling the plug on the Florida server that hosted Voices for Change.

Marita Moll and Leslie Shade call these and other incidents of information-tampering "good reasons for Canadians to be concerned."

The pair, who work with the Canadian Research Alliance for Community Innovation and Networking, recently penned a joint e-mail to The Tyee in which they criticized the conclusions of the Telecommunications Policy Review Panel (TPRC), which delivered a 400-page report last year calling for sweeping changes to Canada's telecom oversight body, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC).

In a nutshell, the panel determined that the CRTC should concern itself with monitoring the social and technical aspects of telecommunications, and leave economic issues up to market forces. Markets are to be regarded as competitive unless proven otherwise, said the panel, a conclusion warmly welcomed by the Conservative government.

But Moll and Shade see the sidelining of the CRTC as having negative ramifications for the industry, and moreover for the public good.

"Telecommunications are oligopolies and do not really engage in competitive behaviour," they wrote. "They own the markets together and they will co-operate in protecting those markets. As such, they have a huge incentive to collaborate to contain bandwidth use to the infrastructure channels they are prepared to provide."

The Big Four

By Geist's count, the biggest four Canadian providers (Telus, Shaw, Rogers and Bell) control 60 per cent of the country's $32 billion telecom market; the top eight control upwards of 80 to 90 per cent. Last week's Canwest-Alliance merger only highlights the how the list of players is shortening.

"There is the real incentive for some of these providers to exclude or diminish the quality of some of the new content that is emerging that I think will increasingly be seen as competitive."

Case in point: the CRTC's favourable ruling for Vonage, an Internet telephone company that complained about a quality of service fee imposed by Shaw, a decision which was overturned by Stephen Harper's Conservative government. Geist is concerned about the fact that the expert panel intended to oversee Canadian telecommunications is increasingly being told to butt out.

"They've actually tried to be hands-on on some issues and got themselves slapped down pretty good by the government."

You don't have to look to Internet telephone to see how the same near-monopolies work with web services. Even if there are eight Internet service providers in Canada, Geist says consumers typically only have the option of choosing between one of two providers for an Internet connection.

"You get cable or ADSL, or nothing," he notes. "That's not a competitive environment at all."

Which means that if in the future companies anger customers the way Telus or Shaw have in the past, "there's little reason to believe that consumers will have options to move to other services if they're unhappy."

Regardless of the situation, telecom deregulation is still "quite clearly the top priority of the Industry minister [Maxime Bernier]," says Geist.

"But the [government's] focus again has been solely one-sided: it's just been on deregulating without addressing these kinds of issues. And there's a certain irony there because this represents by far the best opportunity to build in some net neutrality provisions."

Canada's backwardness in this regard is made all the more apparent given a surprising move by the FCC in the recent AT&T-BellSouth merger. As a condition of U.S. government approval for the takeover, the FCC made both companies agree to respect network neutrality for two years, when clearer-cut legislation is expected to replace the murky language that currently regulates net neutrality in that country.

That move finds no parallel in Canada, where Section 36 of the Telecommunications Act offers no clearer guidance on the topic than the following line: "a Canadian carrier shall not control the content or influence the meaning or purpose of telecommunications carried by it for the public."

Experts like Geist, McArthur, Moll and Shade agree that guideline is as outdated as it is insufficient. In Ottawa last October, Moll and Shade took part in the Alternative Telecommunications Policy Forum, where a panel drafted the following proposal for a guideline: "network operators shall not discriminate against content, applications, or services on broadband Internet services based on their source or ownership."

That clause, meant as an appendix to the net neutrality recommendations in last year's TCRP report, has so far fallen on deaf ears on Parliament Hill.

According to Geist, Industry minister Maxime Bernier has thus far shown "little appetite" for inserting any such language into the Telecommunications Act.

Bernier did not respond to e-mails requesting an interview.

Canadians asleep on issue

For the moment, and judging by every indication, Canada limps into an uncharted electronic future in a near-total policy vacuum on the matter of net neutrality.

That vacuum, twinned with public apathy, is nothing short of a boon for telecom companies, say Moll and Shade, who go on to add that "public policy is obviously serving their needs."

And while the telecom lobbies swamp commissions like the recent TCRP with thousands of pages of testimony, "the few folks sending in submissions in the public interest are barely on the map," they say.

Given that fundamental aspects of how the Internet works are being decided by the PMO, Shade and Moll say it's up to the public to get Canadian politicians "up to speed" on net neutrality the way the American public did in the U.S. To date, there is scarce indication that any of the major parties are thinking about the issue; McArthur says a letter to his Conservative MP in Edmonton didn't even generate a standard response letter. He says only the Green party and the NDP are actively working on net neutrality.

So while many tout the digital revolution as ushering in a new wave of democracy, only 217 of them in Canada have stepped back from the glow and done something to protect it.

"There are lots of things to be really optimistic about online," says Geist, "but this isn't one of them."

Related Tyee stories:

- To Censor Pro-Union Web Site, Telus Blocked 766 Others

- CanCon Adapts to a Wild New Media World

- A Net Abuzz with Activism

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: