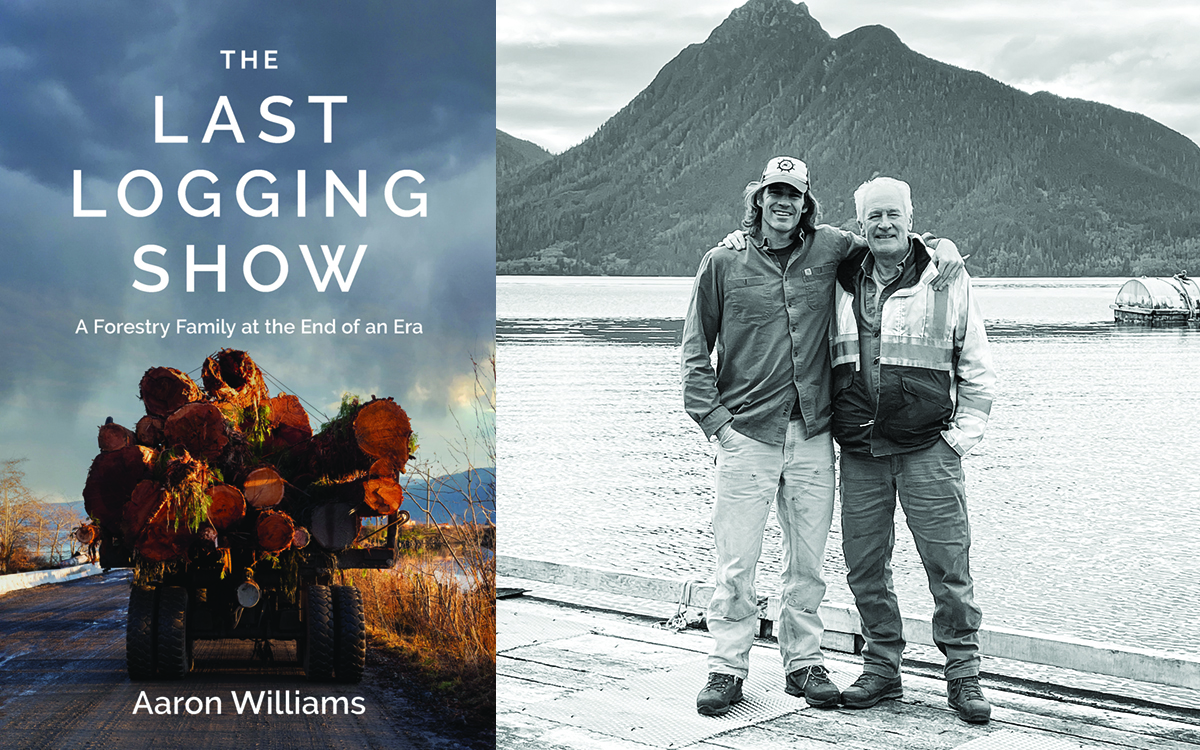

[Editor’s note: ‘By the time I stood on a dock waiting for a float plane to take me to logging camp, my family had been making clearcuts on B.C. hillsides for the better part of a century,’ Aaron Williams writes in the prologue of ‘The Last Logging Show: A Forestry Family at the End of an Era,’ out now from Harbour Publishing. The book follows Williams, a third-generation logger who has mostly found employment elsewhere, as he treks to Haida Gwaii to embed with a mostly aging workforce and document the twilight of conventional logging as a new set of possibilities opens in B.C.’s forests.]

“When you walk up to a tree,” Dave says in a brief moment when his saw is off, “it’s yes or no. You have to ask yourself this question every time you approach a tree.”

“What if it’s a maybe?” I say.

He says a maybe is still a no. A faller has to identify what makes it a maybe and get rid of that problem.

“It’s all about improving your odds,” he says.

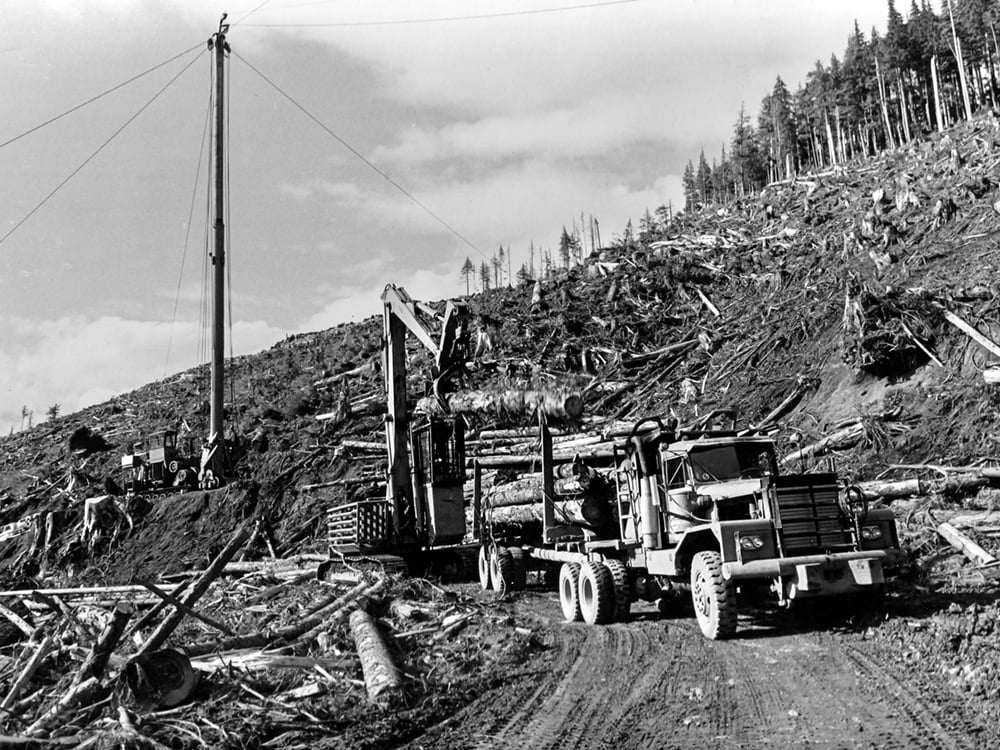

In North America, falling is second only to fishing in terms of danger. For most of his career Dave has made his odds worse by doing a difficult sub-species of the job known as right-of-way falling. This is the falling done to open up new roads to new cutblocks. Fallers working in a cutblock quickly create an opening in the canopy — a safer space — into which most other trees are felled. On a right-of-way, an open space is never achieved. Trees sail through tiny gaps in the forest where there’s a risk they’ll get limb-tied with other trees or brush them at high speed, snapping limbs and tops.

The dangers have not gone unnoticed. For years the provincial government has tried to make falling safer. Decades ago they shortened the workday from 10 or more hours down to 6.5. Stats had shown fallers were often killed late in the day, when they were tired. More recently they’ve been trying out a new training program with longer probationary periods. There are also laminated risk assessment cards fallers are supposed to take into the bush.

“If you need that,” Dave says of the cards, “you’re in the wrong fuckin’ business.”

Late in the morning, Dave is studying the canopy when he turns around. “Wanna fall this one?”

The first tree I cut down was in 2007 on an otherwise wide-open cutblock on a fire in the southern interior of B.C. I remember it because as I got into the back cut my heart started pounding. I intuitively knew I was about to do something that, if done wrong, would kill me. My urge was for flight, to abandon my cuts and get as far away from the tree as possible. If I was alone I would have done it. But because a trainer was watching, my desire to run was eclipsed by a stronger, more dangerous desire to not be thought a coward. The tree went down fine and the ensuing days and years of falling practice dulled that first adrenalin rush. But with falling I suspect the knowledge you’re in over your head never really goes away. At least it shouldn’t. It’s just managed better.

Dave hands me his saw and says, “Make ’er smile,” a reference to the grin-like appearance of a tree trunk branded with an undercut.

Looking up, I see the hemlock is tall — average for Haida Gwaii but, relative to what I’m used to, tall. Through its top branches the sky is high overcast.

Dave’s saw starts easily. It’s a Stihl brand with a 32-inch bar (the blade-like part sticking out from the powerhead). The whole thing weighs less than 20 pounds. His first saw, also a Stihl, an 090 model, weighed closer to 40 pounds. They were capable of handling bars up to 60 inches long.

My dad later recalled for me the tail end of the 090 era of saws.

“If you were in big wood,” he said, “and you were a manly guy, you would go off into the bush with your 090,” at which point you’d run it “until your fingers were see-through.”

It was a glancing reference to what was known as white finger, a painful condition where the vibration of a saw’s handle caused the blood vessels in the hand to constrict, often resulting in nerve damage. Anti-vibration mounts became standard in the models succeeding the 090. Through the decades, saws got lighter and more powerful.

Earlier in the day I’d asked Dave about his saw, the one I’m now holding in my hands. “Feel that!” he’d said, jostling it up and down with two fingers before handing it to me. Lacking his history with the tool I didn’t feel much, certainly not the way he did.

My lack of feeling is validated as the bottom of my undercut comes up short against the top, leaving a dangerous ledge of wood in the trunk. To clean it up, I switch my hand position and change my spot at the base of the tree. I hope these two steps add up to a glimmer of facility, but as I’m fixing my mistake, Dave steps in to give a few pointers. It’s settled: I’m no professional.

You can tell a lot about a faller’s work by looking at the stumps they leave behind. After I finish, we examine mine. The undercut should encompass one third of the tree’s diameter, the back cut the remaining two thirds. Separating these is the holding wood, ideally a straight, narrow line of wood bisecting the stump. My holding wood has issues. A few centimetres at one end are missing. I should have been more patient, but when the tree didn’t fall when I expected it to, I tried cutting at the holding wood. If this tactic was successful, it would have shown some skill. Again, no luck. Because of my botched holding wood, the tree fell slightly to the right of where I intended it to go.

“Aim is everything,” Dave says. He would repeat these words more than once during our time together.

When we’re done reviewing my cuts I hand the saw back to Dave. It feels like I’ve handed a crying infant back to its mother.

Excerpt from ‘The Last Logging Show’ by Aaron Williams. Harbour Publishing, copyright 2024. Reprinted with permission from the publisher. ![]()

Read more: Books, Labour + Industry, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: