[Editor’s note: This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, sustainable economy we need from Alaska to California. Find out more about this project and its funders.]

Fall in Prince William Sound, Alaska, is a stormy affair, with rain, wind, falling temperatures and diminishing daylight. But for kelp farmers like Skye Steritz, it’s a time to be outdoors in rubber boots and rain gear, prepping for the winter growing season. This includes long hours of what Steritz calls “line work,” the labour of stretching lines and building the floating arrays that by spring will support thousands of kilograms of kelp.

“Setting the anchors can be nerve-racking,” says Steritz, explaining that the arrays — rectangular networks of buoys and partially submerged lines — are kept taut through winter with heavy anchors.

Steritz and her husband, Sean Den Adel, live in the fishing town of Cordova, 15 kilometres from their remote kelp operation, called Noble Ocean Farms. They do much of the work with their small seiner, the Lindy. But they contract a larger boat to drop their anchors, which must land on precisely the right bit of muddy sea floor to keep the system under tension.

That’s only part of the job. Weeks prior, the pair sets out in the Lindy to gather sori, or seeds, from wild kelp gardens. At each, Steritz dons a wetsuit and snorkelling gear to cut the sori from ribbons of kelp that undulate in cold ocean currents. The sori go to a hatchery for six weeks to reproduce. When they come back in spools of tiny kelp, Steritz and Den Adel meticulously unravel it onto their lines, where it can grow a metre or more by spring.

Although kelp farming requires no tilling of soil, fertilizer or pesticides during the growing season — all reasons that Steritz and others consider it an environmentally friendly crop — the spring harvest is another busy time. Amid drifting sea otters and migratory seabirds, the pair winch masses of brown kelp aboard their boat, then clean, sort and package it by hand. They sell some at Cordova’s dock, then freeze and ship the rest to a market that they are also building by hand.

“It’s the hardest thing we’ve ever done,” says Steritz. They also hold jobs in Cordova, Steritz as a Grade 4 teacher and Den Adel as a mariculture liaison for a non-profit Alaska Native organization. Still, they believe kelp can bring revenue, resiliency and food security to coastal communities, all while promoting ocean health. Their vision is being put into practice by other seaweed farmers in Alaska and down the west coast, including operations in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon.

Steritz knows the future is uncertain for small growers. And she encourages prospective farmers to reach out to learn from her lessons. And about why, after being spanked by weather, ice and a fickle market, she remains bullish on kelp.

Her enthusiasm is shared among agencies, tribes and others who offer grants and other support for kelp farming. It includes a whopping $49 million for Alaskan mariculture from the Biden administration’s Build Back Better COVID relief program. And while mariculture is a big net that includes growing shellfish, sea cucumbers and more, a focus is integrating kelp into Alaska’s seafood industry.

Last June, federal scientists with NOAA Fisheries also designated Alaska an “aquaculture opportunity area,” deeming it environmentally, socially and economically appropriate for commercial aquaculture, again with kelp playing prominently. Under the designation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration promises help with siting, environmental review and research from its Kodiak and Juneau labs. The goal is a $100-million Alaskan industry in 20 years.

If that seems far-fetched, consider that globally kelp makes up nearly half of all seaweed harvested, and seaweed constitutes the weight of 30 per cent of all farmed seafood. In Indonesia alone, seaweed farms employ nearly a million people, according to Hakai Magazine.

“We have a lot of alignment behind kelp,” says Dan Lesh, deputy director of Southeast Conference, the federally designated economic development organization for southeast Alaska that leads distribution of Build Back Better funds.

The alignment was clear when NOAA held Alaska-based listening sessions ahead of its aquaculture designation. Fishers, tribes, residents and community governments all spoke up for sustainable aquaculture.

Lesh explains that to many, kelp promises a predictable and sustainable industry for coastal communities, which have long weathered the volatility of logging, mining and fishing. He describes practical factors, too, like Alaska’s huge coastline — more than the contiguous United States and B.C. combined — that hosts many sheltered bays like the one permitted to Noble Ocean. Alaskan waters are also expected to remain cool enough for kelp in a warming climate. And with widespread support, Alaska offers a friendly permitting environment.

The suite of pluses stands out on the West Coast. Washington, which already has a lucrative mariculture industry largely devoted to shellfish, is slower to embrace kelp farming, while long stretches of Oregon and California have open coasts inhospitable to farming. British Columbia has similar geography to southern Alaska and a growing kelp industry, but not the same tide of government backing.

Another advantage, says Lesh, is Alaska’s $6-billion commercial fishing industry. Kelp farmers have hooked into its buoys and lines and the fish totes that now transport their harvests. There are boats, too, like the old seiner that Steritz and Den Adel run, and the former gillnetters and tenders tied up at Alaska’s growing number of farms.

Markos Scheer, CEO of Seagrove Kelp near Craig, in southern southeast Alaska, says that the fishing gear brings a workforce accustomed to working safely around rough seas. As Alaska’s largest kelp producer, Seagrove needs that assurance as it hires refrigerated tenders to ship over 100,000 kilograms of kelp to processors nearly 300 kilometres away in Ketchikan.

Scheer says that because kelp is planted in fall and harvested in spring, it coincides with lulls for commercial fishers, who can diversify their businesses by moonlighting as farmers or transporters.

Data suggests all this is working. Alaska reports the acres permitted for kelp rose from fewer than 350 in 2016 to nearly 1,300 in 2022. Dozens of farms, mainly between the Aleutian Islands and Ketchikan, produced nearly 400,000 kilograms of kelp in 2022, making Alaska second only to Maine in the United States.

For Steritz, who has loved the ocean from her youth, kelp is exciting for more than its economics. She sees it as a regenerative crop that’s healthy for both coastal people and the waters they rely on. She says it can also improve food security for remote communities like Cordova, where a food supply relying on ferries, barges and planes struggled during the pandemic.

Kelp as a superfood

Eating kelp is nothing new. For thousands of years, it has fed Indigenous people from Baja to Alaska, with varying species eaten raw, steamed or used to season or preserve fish. Early Pacific Northwesters used bull kelp’s long stipes — the durable stems rising over 60 metres from the ocean floor — for rope, fishing line and more.

Western science was slower to recognize kelp’s value. But now anthropologists believe human migration along western North America followed a “kelp highway,” where people leapfrogged southward among forests of floating bull kelp that provided calm water and abundant foods. It highlights the exceptional habitat value of kelp forests, which shelter juvenile salmon, spawning herring, snails, crabs, urchins and many others that attract fish, birds, marine mammals and people.

Long popular in Asian diets, kelp is also a reputed superfood packed with vitamins and minerals that some say could provide an alternative to meat in the climate crisis era. According to the United Nations, its rapid growth with no need for arable land could help feed a burgeoning human population.

Kelp also sequesters carbon and provides food and livestock feed without tapping fresh water or requiring chemical additives. And it buffers local waters from the ocean acidification caused by carbon dioxide emissions, which harms shellfish. In Washington, some oyster growers affected by acidification now co-produce with kelp to protect harvests.

Other superpowers include preventing erosion, oxygenating coastal waters and a seemingly insatiable ability among some species, including the ribbon kelp grown by Steritz, to absorb nitrogen from sewage and agriculture runoff.

But while kelp may fight climate change, it can also fall victim to it, with a decline in kelp forests in parts of Washington and southern B.C. attributed partly to warming. And the spectre of large-scale farming may bring its own concerns, including invasive species or displacement of activities such as subsistence fishing or recreation.

With much unknown, Steritz and others work with researchers to better understand kelp’s services and how to best produce it. And she occasionally carries handfuls of it into her classroom to show students something of what the future might look like.

‘We’re working toward a larger industry’

While excitement swirls around kelp, Lesh acknowledges it’s a risky sector, especially for small farmers. He says a top challenge is Alaska’s distance from the roads, rails and markets that have lifted Maine’s industry. And while commercial fishers lend eager support, kelp lacks the big processors, transporters and markets that drive Alaska’s seafood industry, leaving small farmers like Steritz to process and distribute their harvests to markets of their own making.

Build Back Better is designed to help through market stimulus, infrastructure, training and research and development. But such things take time, and the gains can feel elusive for small farmers like Steritz.

“We’re working toward a larger industry,” says Lesh, explaining that aside from food products, kelp holds promise for bioplastics, biofuels, cosmetics, fertilizer and more. The industries are large enough that Alaskan kelp only needs to capture a niche to achieve viability, he says.

Yet tapping those markets from Alaska — and competing globally with long-standing Asian or even Maine producers — is difficult. Nevertheless, Steritz has cobbled together buyers for food, compost and bioplastics, with 70 per cent of sales in Alaska.

Matt Kern, co-founder of the Juneau-based Barnacle Foods, also knows kelp’s challenges. Kern and his partners started the company in 2016, harvesting wild kelp before Alaskan farms even hit the water. Since then, they’ve approached the market with the tenacity of their namesake crustacean.

“We want kelp to become a household name,” says Kern, whose company offers 25 kelp-based products, including salsas, sauces, spice mixes and more that are available online and at 1,500 retail outlets, ranging from grocery stores to Alaskan airports.

It works because Barnacle is also a processor. Its 700-square-metre facility can freeze 5,000 kilograms of kelp daily, which they then use to create products throughout the year. They also have limited drying capacity.

Kern explains that a root challenge with kelp is its seasonality. Unlike fish, where different species reach the dock over months, kelp shows up in one slug in the spring, when farmers like Steritz must pull it from the water before it overripens.

Additionally, says Kern, kelp’s short shelf life requires freezing or drying it within 24 to 48 hours. But as a processor and manufacturer, Barnacle can purchase bulk from local growers, relieving them of processing and marketing. Similarly, Seagrove near Craig works with a Ketchikan processor and partners who use kelp for skin care products, foods, fertilizer and more.

Cascadia Seaweed on western Vancouver Island, Canada’s largest kelp producer, offers another model. It takes in kelp from 10 B.C. farms, then works with nearby processing and manufacturing partners to create climate-friendly feed supplements for cattle and bio-stimulants for gardens and farms. It is also building processing and manufacturing capacity in Prince Rupert, where its products can access global markets via container ships or continental roads and railroads.

These examples show nodes of kelp production and processing forming along the coast. But farmers in Prince William Sound and other remote areas still lack regional processors.

“It’s going to take a lot of effort and resources to build the industry,” says Kern. He’s optimistic that both large and small farms will work, but he cautions that logistics and market access will limit growth for now. Still, he calls kelp “a tremendous opportunity to diversify our coastal economy.”

Keeping up with the kelp rush

In remote Alaska Native communities, where the connection to seaweed stretches back through time, people mull whether to join the kelp rush. Hoping to avoid past mistakes, when small Alaska Native communities missed out on industries that used their traditional lands and resources, Build Back Better directs 25 per cent of funds to Alaska Native participation in mariculture. Another 25 per cent goes to underserved rural communities.

A statewide mariculture liaison program helps connect rural and Indigenous communities to information and resources. Den Adel is one of two liaisons for the Chugach Regional Resources Commission, which supports natural resources and economic development in Alaska Native communities in Prince William Sound and lower Cook Inlet.

“Some communities want to get involved,” says Willow Hetrick-Price, executive director of CRRC. But opinions vary, she says, with some people skeptical, uncertain or more interested in growing kelp solely to benefit local salmon and other resources.

Hetrick-Price explains that remote communities must weigh their available time, energy and skills, along with their appetite for pursuing a new business. But there’s concern, too, that if they don’t bite now, outside interests might land nearby farm sites.

But they’ll have backing from CRRC, where Den Adel and others chase grants, attend conferences and trainings and visit sites in Maine, B.C. and beyond to tap the latest knowledge.

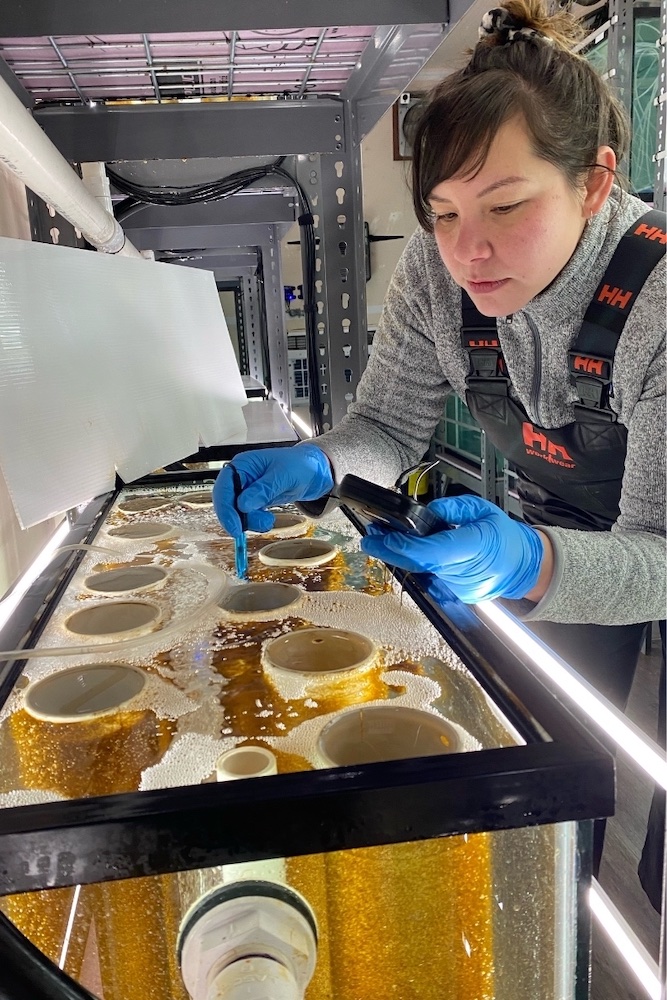

Support also comes from the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, a hatchery that CRRC acquired in 2002. At its aluminum-sided building in Seward, between Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet, staff conduct wide-ranging work tied to subsistence and natural resources, including growing kelp seed for Noble Ocean and others. They also raise shellfish to restore or enhance populations, help monitor acidification impacts and test for biotoxins in wild shellfish.

While Alutiiq Pride staff share the excitement around kelp, they also want to see more science. With funding from the Exxon Valdez oil spill settlement and a range of statewide partners, they’re studying its local potential to buffer acidification and improve ocean health.

Hetrick-Price says it makes for a dizzying amount of work, writing grants, managing projects, nurturing relationships and ensuring villages have the best available resources.

“It’s all great stuff,” she says, including the Build Back Better commitment to tribal engagement. “But some of it is moving too fast and too furious for our communities to meaningfully engage in.”

As they weigh options, Hetrick-Price knows that some worry kelp will be another “speeding train” of opportunity they lacked the time to latch on to.

CRRC represents just one group of Alaska’s varied Indigenous communities, each with their own factors to consider. Likewise in B.C., where seven First Nations communities now grow kelp for Cascadia Seaweed’s agricultural products. From his perspective, Cascadia Seaweed CEO Michael Williamson values the partnerships and says they produce local jobs and diversified revenue that keep people connected to the ocean.

In spring, the bay where Steritz and Den Adel grow kelp is calm. Spruce and hemlocks crowd an uneven shore and cast green reflections onto waters that are busy with otters, seals and seabirds. A receding tide reveals a rocky intertidal draped in seaweed, sea stars and shellfish, where oystercatchers and ravens rummage through a bounty that has fed people here for millennia.

Steritz describes it as a joyful time of year when she and Den Adel size up their harvest, along with the life teeming around it. Later, arriving back in Cordova, eager buyers meet them at the Lindy.

“Cordova has really shown up to support us,” says Steritz.

Despite all the uncertainty, these moments reinforce the vision of local kelp feeding communities, perhaps appearing one day on school or hospital menus, says Steritz.

Until then, the pair and others like them will keep figuring out what works, aided by government grants, community effort and a measure of the scrappy resourcefulness embodied by Steritz and Den Adel, whose first arrays incorporated stray buoys washed up on Alaskan beaches, anchored down by decommissioned train wheels from the Alaska Railroad.

Their latest move is working with a local researcher to investigate whether excess heat from the diesel generators that supply Cordova’s electricity can dry their kelp. The heat will be piped into a new insulated structure where Noble Ocean and another farm will use tumblers to dehydrate their 2024 harvest.

If it works, shipping will become easier and less expensive. If not, they’ll move to the next idea. And like others along the coast, they’ll share their results to keep kelp farms moving forward. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: