The news came on a Thursday: Vice Media was shutting down.

It was Feb. 22, 2024, and the writing had been on the wall. Last May, the company had filed for bankruptcy protection and was sold to a consortium of its former lenders. Budget cuts, show cancellations and layoffs followed. The shutdown would be the final blow.

But the company’s journalists received more bad news that day, an anonymous tip that supposedly originated from someone in management: Vice’s website would be deleted entirely.

Could it be possible? Surely not, thought some reporters, as doing so would violate a legal hold on certain stories with potential or pending litigation.

Matthew Gault, the Columbia, South Carolina-based host and producer of the Vice podcast Cyber, believed it could happen. Vice staffers also lost their ability to download emails that day — not a good sign.

“C-suite was so ignorant and divorced from the day-to-day goings-on of the site that we would not have been shocked for them to have pulled it down,” he said.

Years of work, reports in the thousands, were at risk. It would have been a blow to the journalists themselves, but also to the public.

Vice, once heralded as the future of news, made a name covering culture and current affairs for millennials, an audience that legacy media struggled to capture in the digital space.

Here in Canada, Vice dedicated resources to a number of beats often neglected by mainstream media, from extremist groups to battles over Indigenous land rights.

In the wider media landscape, it wasn’t the only bold experiment that had fizzled out.

In 2016, the snarky Gawker went bankrupt after Hulk Hogan successfully sued the outlet for publishing his sex tape, and its new owners were unable to launch a comeback. In 2023, BuzzFeed closed its Pulitzer-winning news division.

Vancouver’s media industry has experienced its own share of sales, shutdowns and shrinkages in recent years.

Gone are the websites of the Westender (d. 2017), Metro (d. 2018) and the Vancouver Courier (d. 2020). The Georgia Straight has survived, but not before its new owners fired its senior staff in 2022. The Vancouver Sun, the long-running daily, ditched its digs in 2023 and no longer has an office in the city.

It continues to be a dire time for old and young outlets alike. And with these closures, you never know when a repository of news — political shenanigans, hard-hitting investigations, cultural portraits, Little League stars and so many community voices — might vanish from the internet overnight.

So Matthew, worried that the work of his Vice colleagues would be lost forever, helped kick off a rescue mission.

His wife, Karen, who works in geographic information system software engineering, had always been telling him to save his work. Unlike the average journalist, she had the professional skills to help the Vice team do so on a large scale.

“If the work that you’ve been doing for the last five years doesn’t exist, and you didn’t save it, what do you do?” said Karen. “All these journalists are going to be looking for jobs and all the places they’re applying to are going to want to see examples of their work.”

It turns out that others had pulled off such an archival mission before.

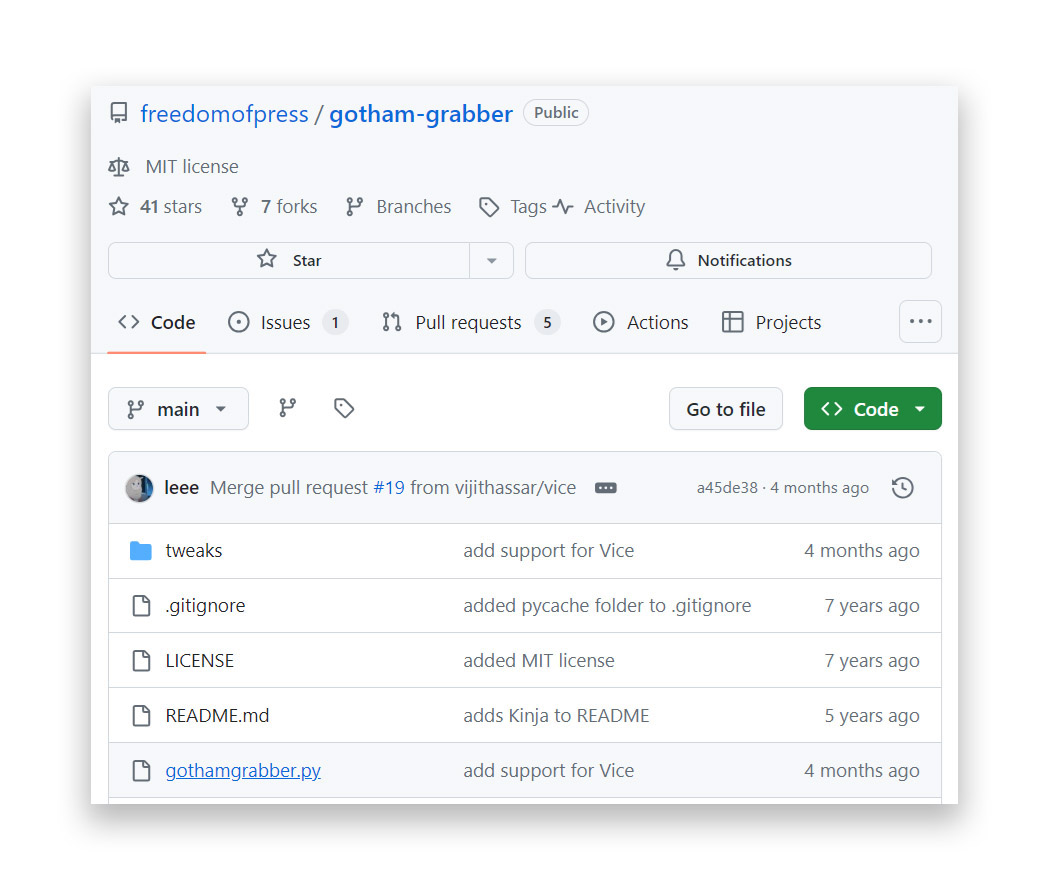

Karen stumbled upon a tool used to save stories from the Gothamist and its family of online outlets across the United States, known for their hyperlocal reporting: the LAist, Chicagoist, DCist and SFist. Back in 2017, a new owner had shut down those news sites a week after staff unionized.

The tool was a set of scripts called “Gotham Grabber” designed to save PDF versions of stories from the sites en masse. The scripts save individual journalists from having to right-click every single page to save their work, a tedious task that would have been near impossible for those who had authored stories in the hundreds.

Gotham Grabber proved to be so useful that people from a number of other publications, from Newsweek to LA Weekly, adapted the scripts to scrape stories from their respective websites.

On Friday, the day after the shutdown announcement, the Vice site was still up. So Karen quickly set her own adapted version of the script to work.

The Gaults were anxious all weekend.

Matthew had been taking requests for PDFs from a growing number of colleagues via a Signal messaging group they had created called “the Great Vice Scrape.”

“We only got a few hours of sleep,” he said. “We were worried that we would wake up Monday morning and the site would be deleted.”

Karen monitored the script as it pulled the work of one journalist after another, hoping that it wouldn’t catch the attention of someone at the company with the power to stop them, or a function that would automatically block her IP address.

“Any time you’re scraping something, you’re worried about them noticing a lot of traffic hits and blocking you,” said Karen, who had the PDFs saving at a subtle pace.

I had also been watching the saga of the Vice shutdown unfold that weekend, as Canadian freelancers who were not connected with the Gaults rushed to save PDFs of their stories by hand, taking to Twitter to lament the potential loss of their work.

When Monday arrived, the PDFs had all been saved.

To the Gaults’ surprise, the Vice site was still up. To this day, you can still visit Vice online, though there are no new stories.

Whether there was any truth to the rumour or not, the scramble highlighted the precarious nature of digital news and the importance of archiving for journalists and newsrooms alike.

“When you’re waiting to get laid off, your mind isn’t necessarily able to focus on a big project like this,” said Matthew. “You’ve got other things on your mind.”

The couple was able to pull off the rescue mission, but not everyone can do so in a pinch.

How to preserve works of journalism for the future before a crisis hits?

What journalists are (and aren’t) doing

I have to admit, I’m not very good at saving my work.

The hard copies are scattered between my parents’ house, the Tyee office and a storage locker. As for my work for digital outlets? No archive exists.

I couldn’t help but be impressed by the habits of my Tyee editor Jackie Wong.

“Hard copies of the urban weekly where I worked went into a big blue Rubbermaid Roughneck storage bin in the closet,” she said. “I did the same with copies of the magazines carrying my freelance work, and I kept a now-defunct Blogspot blog of my other published work online.

“But in a sudden move spurred by a dramatic relationship breakup when I was 30, the bin of newspapers got lost. Then, while settling into a new apartment and using a stack of moving boxes as a bedside table, I spilled water on my laptop, killing its hard drive and its contents.”

Asking other colleagues in the industry about how they keep their personal archives, I don’t think the average journalist is quite as organized as Wong.

“Please don’t ask me that — it’s so bad,” Jimmy Thomson, a Victoria-based journalist and journalism instructor who recently took a job as managing editor of Canada’s National Observer, told me. “I sporadically have a little moment of panic that something bad is going to happen to my stories that are online.”

All journalists working in this age will have experienced the loss of work they’ve produced. Those who kicked off their careers in the digital era are too used to outliving the shuttered outlets where they cut their teeth. Or an important story of theirs may be still online but has started to “rot,” a term used by internet experts to refer to dead hyperlinks. Embedded elements from third parties like Twitter or Instagram could also vanish at the whim of their owners or individual users.

This is also an age in which staying at a journalism job for decades is unusual, and as a result, journalists are dealing with many more employers with different archiving practices (if they have them at all) over the course of their careers.

However, taking the time to create a comprehensive archive of one’s work is often an afterthought, insurance we don’t know we need until it’s too late.

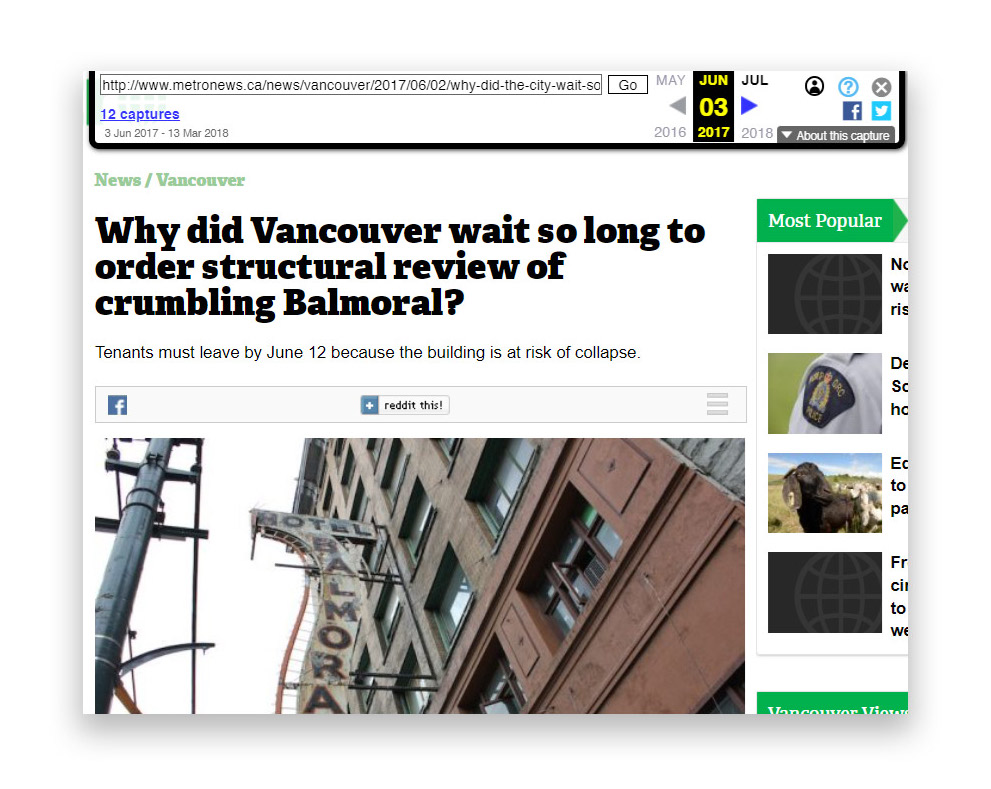

Another Tyee colleague, Jen St. Denis, lost a large body of work as a staff reporter for the Metro commuter daily when it was rebranded as the short-lived Star Vancouver. Everything she wrote before the 2018 rebrand vanished overnight.

“It was heartbreaking at the time, but I’m still feeling the loss years later,” she said.

When St. Denis was reporting on the fire at the Winters Hotel for The Tyee, she realized that she had previously met one of the victims who had died in the blaze, Mary Ann Garlow, during her Metro years. However, that story, along with all her others, had been taken down with the site.

“It was only through the Wayback Machine that I was able to retrieve Mary Ann’s quote and what she had told me about living in the Downtown Eastside at the time to be able to add to a story about her death.”

Should journalists be saving our work daily? Or at least monthly? In what format? Where to store it? Are multiple copies necessary? And do we still need to do so if our employers have a robust archival system of their own?

Journalists are already being asked to do more than ever before in our digital age. In addition to reporting, we are photographers, video editors, social media managers and, in small newsrooms, the ones who manually enter stories into content management systems to be published on the web. Should we be adding archivist to our list of jobs?

It doesn’t help that the digital world and digital news are so focused on presenting information for the now, without much thought for the future. Everything from the written copy to the user experience is tailored to the hardware and software of the present moment.

On top of that, there’s journalism’s struggle to simply survive and keep finances stable until tomorrow.

“Having run a small newsroom, I know how close your nose gets to the grind,” said Thomson. He is the former editor of the online outlet Capital Daily. It’s hard to find the capacity to consider what needs doing beyond the consuming work of keeping a daily outlet afloat.

“If you don’t know that you’re going to be open in a year or have the revenue to keep paying everyone next quarter, how are you thinking about the future needs of the reporting that you’re doing today?” he asked.

“We’re just running around with our hair on fire.”

The digital decay

One of the problems with keeping accessible archives of news on the internet is the cost and the return.

“You don’t necessarily get rich from trying to save history,” said Katie MacKinnon, who has a doctorate in information studies.

Journalists like me often ask why the owners of defunct outlets can’t just leave the news on the web rather than take it down. Surely it would be inexpensive?

However, MacKinnon and others in her field say that maintaining a website with no new content would still require human labour, security and upgrades to keep up with the evolving internet, and the owners might not see a material benefit to doing so.

In an article on the subject, Slate suggests that it would cost a few hundred dollars a month.

A scary way for owners of content to make money is to sell their data sets of news to AI companies hungry to gobble them up to train their products.

Online news is part of the digital world and therefore susceptible to the problem of data loss, something that has become so commonplace in our lives that we don’t often think about the implications.

“We experience it on a daily basis,” said MacKinnon. “We lose access to things, things get deleted and the stuff we spend time on gets destroyed. It’s the very nature of working in a digital economy. A lot of the time it’s just a mild annoyance, but these things are happening at an infrastructure level and on a very big scale.”

MacKinnon is a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Copenhagen studying these questions as part of the Data Loss research project, investigating an array of challenges such as link rot and aging programs. The researchers are also interested in how individuals, organizations and governments respond to data loss: its disappearance, its destruction and its dispossession.

Data loss is “deeply unjust,” says her colleague at the university, Nanna Bonde Thylstrup. Non-profits and public institutions struggle to find money to make digital knowledge accessible to all, which means that how these issues play out is left to politicians and profit-driven corporations.

“Understanding these forces is a critical step toward managing, mitigating and ultimately controlling data loss and, with it, the conditions under which our societies remember and forget,” she wrote in the New York Times.

Industries where there are mergers and acquisitions around data and platforms are particularly susceptible to data loss, says MacKinnon.

The journalism industry is such a place. And though outlets are engaging in work for the public interest, that doesn’t necessarily mean they are committed to ensuring that information is accessible far into the future, especially if they are a for-profit enterprise.

“Traditional news media is different. It’s something that gets distributed in paper copy and then materially spreads far and wide,” said MacKinnon. “But if digital news is down, then it doesn’t exist.”

Universal access?

As outlets come and go, the Wayback Machine has been relied upon to go back in time to visit web pages as they looked on a particular day in history. The tool was created by the San Francisco-based non-profit Internet Archive back in 1996, intended to provide “universal access for all knowledge.”

The non-profit is considered one of the stalwarts of the internet and is still going strong, having archived over 145 petabytes of data, including 835 billion web pages, as of the time this article was published.

However, it works only if the Internet Archive has created a “snapshot” of that web page on that particular day. The tool does so automatically, though internet users can manually submit requests for a web page to be saved, either by visiting the site or by using the Wayback Machine’s browser extension.

It’s a popular tool for a great diversity of researchers — and one commonly used to look at old news, like when my colleague Jen St. Denis went searching for her lost interview — but the Internet Archive isn’t perfect either.

It is unable to save paywalled content, and changes might have been made to a web page in between snapshots.

Not every outlet is the size of the New York Times, which has its own archives. The Internet Archive is a non-profit digital archive open to partnerships with institutions to accomplish its lofty mission of building a digital library of internet sites and digital artifacts.

It is refreshing to have the Internet Archive as a model when many other archives of news are owned by companies. The Canadian Newsstream is owned by ProQuest, whose parent is Clarivate, an analytics company. Newspapers.com is owned by Ancestry.com, whose parent is Blackstone, an investment management company.

While public institutions that step into the role of archiving news might be free from the profit motive, funding is still an issue.

If large publications with deeper pockets are the ones with the most secure and extensive archives, journalist Thomson argues, it can affect the public’s view of history in the future.

He gives the example of a legacy publication like the Globe and Mail, which described itself as targeting households with incomes of $125,000 in its marketing back in 2013. Compared with a number of online outlets, the perspectives and the demographics of its staff are not as diverse.

And yet, “the voice of the Globe and the perspective of the Globe are overrepresented in our archives compared to those from the online ecosystem,” Thomson said.

That’s why he believes that the loss of digital outlets with greater diversity — whether in their hiring practices or, like Vice, championing new and neglected beats with a modern tone — would also be a “blow to equity.”

Backing up history

So, what should journalists be doing to archive their journalism?

“Try and actually keep a record as though you are an archivist for your own work because no one else is going to be,” said Thomson. “This used to be a default part of the publishing process [but] we don’t have built-in archivists and librarians in newsrooms anymore. You have to be that for yourself.”

“For individuals, I would definitely recommend to keep your stuff — and keep it in multiple formats,” said Claire Battershill, an associate professor in the University of Toronto’s faculty of information.

And don’t discount hard copies, she says, which has been proven through not just the digital age but the microfilm boom of the 1980s and ’90s. “One thing about paper is that it actually lasts very well.”

In addition to the PDFs generated by the Gaults as part of the Great Vice Scrape (each file in the hundreds or thousands of kilobytes), one of their friends created simple versions of stories as HTML documents (each file in the single or double digits of kilobytes). This method might lose the look of the original web page, but it keeps storage small.

Battershill says that journalists should ask their employers about their archival practices: “Do they have a relationship with a university or institutional library archives where stuff is being deposited?”

Also, journalists should take the time to learn about coding, data and digital security, suggest the Gaults. The skill set is useful not only for archiving your work, but also for reporting. They recommend the 2024 book Hacks, Leaks and Revelations: The Art of Analyzing Hacked and Leaked Data by journalist Micah Lee, who spent a decade at the Intercept.

Our personal archives as journalists are never going to be perfect. But they hold special importance because they are collected by real people, and it’s important for the Internet Archive and other institutions to incorporate material from people who made conscious decisions to save something, says MacKinnon, as opposed to automatic “crawlers” that search the web.

Digital data donated by individuals, just like any physical newspaper or magazine collection, could become a larger resource for archives in the future.

Thomson describes the unique intersection of career-related tensions that journalists wrestle with on a daily basis. They’re everyday challenges that carry long-term consequences.

“There is the micro perspective of ‘I’m trying to get a job,’” he notes. “And then there’s also the big, grandiose perspective of ‘This is the first draft of history.’”

We better start saving. ![]()

Read more: Media, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: