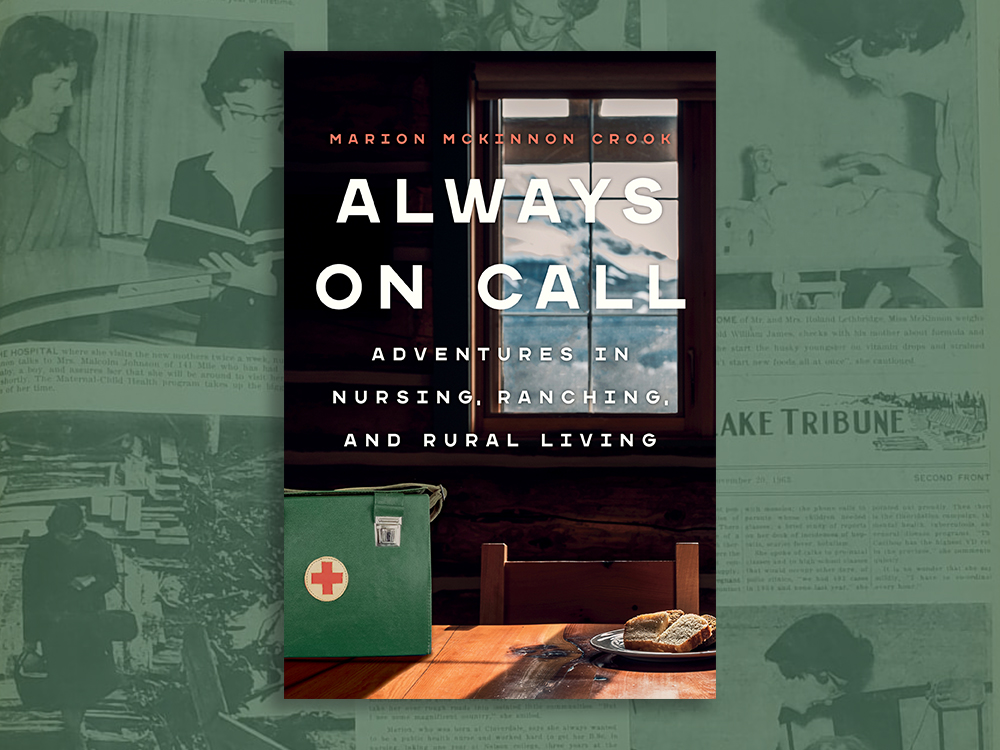

[Editor’s note: Marion McKinnon Crook arrived in the Cariboo in the 1960s, fresh from earning a bachelor of science in nursing. ‘Always Pack a Candle,’ which covers her early years in the region, won the BC Historical Federation’s Community History Award in 2021. ‘Always on Call,’ Crook’s followup, is an account of her life a decade later, in the mid-1970s, with more experience behind her — but still much to learn. In the excerpt below, Crook learns about how to do a better blood draw while attending to the entire local hockey team.]

“We have to deal with the Stampeders, Marion,” Angela told me one Monday morning as she popped her head into my office.

The local hockey team took their game seriously. There was a snarling rivalry between the Williams Lake Stampeders and the Quesnel Kangaroos. I didn’t expect to be involved in any capacity other than as an onlooker from a seat in the arena.

“One of them has mono,” she continued.

I waited, knowing there would be a task for me in her announcement. I’d been sitting at my desk conscientiously reading one of the many reports that appeared in the wooden inbox on my desk every morning. The central office in Victoria expected every public health nurse to have current knowledge of many diseases, as well as the updated and changing policies. I was much more interested in the hockey team, so I happily put down the directive on how to tabulate nursing statistics.

“We don’t see that often,” I said.

“The players are at a vulnerable age. Dr. Anderson is concerned and the manager is worried the whole team will get it.”

I conjured up the page on mononucleosis in my Communicable Diseases in Man text. I’d memorized large portions of that book as a student. Mono was contagious, but not highly contagious.

“It’s transferred in saliva,” I remembered. It’s sometimes called the kissing disease. I’d have to forget that term when dealing with the hockey team.

“They probably share water bottles,” Angela said. “Or towels.”

I could see how the team might be more vulnerable to infection than most people. “What do they want us to do?”

“Take blood from the whole team. You’ve taken blood before. You should be competent.”

Nurses knew how to withdraw blood but usually left that chore to the lab technicians. But I took blood every Monday from inmates at the jail, where everyone had to have a test for syphilis. Usually, the prisoners were young men with big, accessible veins. The hockey players were a similar age group. It shouldn’t be hard. The challenge would be in setting up a special clinic and getting everyone to arrive on time.

“You can deliver the samples to this lab at the hospital, where they’ll test for antibodies.” Angela gave me instructions.

“I’ll call the lab so they can block off some time to deal with it. How many people will there be?” I asked.

Angela looked at her notes. “Twenty-two players, two referees and four management staff. I’ll get Ellie to type up these notes. The manager is Robin Ferris. You can tee it all up with him.”

Within the hour, Ellie had typed up the notes and placed them on my desk.

I reached for the phone and contacted Robin Ferris. He wasn’t a full-time manager — no one was full time, neither management nor players; they all had other jobs. Robin Ferris owned a garage and auto repair shop.

“Hell of a thing,” he said on the phone. “Big strapping lad. Weak as a kitten.”

“It hits some people like that. I hope he’s getting rest. That’s the treatment.”

“Yeah. He boards with my sister and she’s looking after him. I’m worried that more guys are going to come down with it. I don’t want them playing when they’re sick, but I need to field a team to meet Quesnel this weekend. Hate to forfeit that game. Quesnel’s at the top of the league. Lose this Friday and we won’t have a snowball’s hope in hell at the trophy.”

“The lab results usually come back in a day or two,” I reassured him. “If we could hold a clinic here tomorrow at the health unit, it will give the lab time to get the results back to me, then to you, before Friday.”

“Sounds good. What time?”

We arranged for an after-hours clinic at 6 p.m. the next day. That was as quick as I could manage to get it organized. I asked him for two volunteers to help with the clinic and gave Robin some advice. “You need to make sure the players and staff don’t share towels, water bottles or anything that might come in contact with their mouths.”

There was silence for a moment, then he said, “I can do that.”

‘He fainted’

The next night, the waiting room was filled with young men of every size and shape: tall and broad, short and chunky, wiry, thin and even chubby. The first volunteer, Thelma Parks, the wife of the assistant manager, helped by keeping order and demanding everyone fill out their requisition slip. The second, designated to help me in the much quieter treatment room, was Peggy Ferris, Robin’s wife. I knew Peggy as she was the receptionist at the elementary school and would be used to handling everything from playground accidents to truants to hallway fights. She’d be efficient.

I had my syringes, needles, sample tubes, rubber tourniquet and alcohol swabs on my desk. Peggy had a table beside me with a pen and tape. She would take the requisition from the patient, write his name and requisition number on the tube, and hand it to me. When I had taken the sample, I’d pass the filled tube over to her. She’d tape the requisition to it and place it in the insulated container beside her. It was important not to mix up any of the samples or end up with unlabelled samples. It was an orderly process, and I expected it would go smoothly.

All went well until Wayne Abbot shuffled in. He was about six foot two, bulky and cheerful.

“Hi, Wayne.” He worked for Robin at the garage; I often saw him when I got gas and had my car serviced.

“Hiya, Mrs. Crook. How’s it goin’?”

I smiled. “Pretty good. Just give Peggy your requisition.”

He did that.

“You can sit here.” I waved toward the chair.

“Nah. I’d rather stand. Seems easier, somehow.”

He seemed relaxed, so there wasn’t any reason not to accommodate him. I stood as well.

“Just rest your arm on the gurney here.” I indicated the padded stretcher against the wall.

Peggy handed me the sample tube with Wayne’s name written on it. I picked up an alcohol swab and the tourniquet. I wrapped the rubber tourniquet around his arm and picked up a syringe with an attached needle.

“Just open and close your fist a couple of times. That’s right. Lovely veins.” I slipped the needle into the vein. Easy.

“Watch out!” Peggy called.

I looked up just in time to see Wayne’s eyes roll back and his body start to slide sideways. I grabbed him by the shoulder with my left hand and eased him to the floor — very quickly as he was so heavy he could pull me down with him. The needle was still in my right hand but no longer in Wayne’s arm.

“What happened?” Peggy asked.

“He fainted.” I dropped the syringe into the basin on my desk, then checked Wayne’s colour, his breathing and his heart rate.

“Hand me another syringe, please, Peggy.”

She plucked a prepared syringe from my desk and passed it to me. I found Wayne’s vein again, released the tourniquet and withdrew the blood. I shot the blood into the sample tube and handed it to Peggy. I was wiping Wayne’s arm with alcohol when he blinked.

“All done,” I said in case he was worried he’d have to face a needle again.

“Ah, shit,” he said. “I hate blood. You won’t tell the guys, will you, Marion?”

If he’d told me that at the beginning, I’d have insisted he stay seated. He could have injured himself or given me some bruises. But I wasn’t about to make his day worse.

I glanced at Peggy. She was suppressing a grin.

“I won’t tell a soul,” I said.

He sat up and got to his feet. We eyed him warily, but he had good colour and was intent on leaving.

“Uh, thanks,” he said.

“He’s such a baby,” Peggy said with affection after he’d gone.

“He’d hate to know we thought about him that way.”

“I won’t tell him.”

I took a couple of deep breaths. There were about 20 more in the waiting room. This was going to take some time.

I thought about where I usually was at this time of the day — home. Carl was with the kids. He was on Cleo duty but had assured me when I’d called earlier that the pig and piglets were fine. None of my sheep had started to lamb, and he’d manage supper. I ceased to think about home.

We worked until eight. I thanked Peggy and Thelma, loaded the samples into my car and drove in the dark, cold evening. It was only a six-minute drive to the hospital lab. When I got there, I delivered the samples to the night orderly who was expecting me.

“Andrea told me where to put them. She said thanks for collecting the blood. It saved her all kinds of time.” Andrea, the lab technician, had probably gone home at 5.

“No problem,” I said. I was immensely satisfied with the work I’d done that day. I liked doing practical tasks that made a difference in the community.

“She’ll call you.”

I drove home along our gravel road. The headlights picked up the white of the snow still in patches by the roadside. I was the only driver on the road. It felt as though I was alone in the universe.

Andrea did call me early in the morning two days later.

“Can you come up here?” Andrea’s tone was serious. She didn’t give me the results of the tests.

“Sure.” I left the office and drove up the hill to the hospital. What had gone wrong? Were there many cases of mono in the team? Would I have to deliver bad news to Robin? The game was tomorrow.

‘I thought about resigning’

Andrea was in her 30s and had been the lab technician at the hospital for years. While I knew how to get blood from patients, she knew everything about how to test it, preserve it and report on it.

It wasn’t the results that were bothering Andrea.

“You hemolyzed the whole lot,” Andrea said.

I looked at her, stunned. I didn’t even know I could do that.

“You must have shot the blood into the tube too fast. All the red cells clotted.”

I sat down on a chair with a thud. I could see Robin Ferris’s face as I explained I’d made a mistake and would have to arrange another clinic and take blood from every one of those young men again. I couldn’t do that and get the results by tomorrow. They’d have to forfeit the game. Hard on them and hard on me. Robin would think I was incompetent. That information would fly around town like wildfire and everyone would think I was incompetent. Well, I had been. I hadn’t known I could hemolyze the sample. Should I have known? Probably. But I hadn’t. What about the samples I took every week at the jail? But I didn’t shoot the blood into the sample vial at the jail because I never felt rushed there. I’d only done that with the hockey team. Wayne would have to go through it again. I was not going to be his favourite person, or anyone’s favourite person. I thought about resigning.

“I have to do it all again,” I whispered. What would Angela think of me? What would my colleagues think of me? I bit my lip and tried to concentrate.

“No,” Andrea said. “Luckily, it didn’t interfere with the test. We could still use the samples. The results were all negative.”

“Oh, thank God!” The relief was incredible. My hands tingled. I took several deep breaths. I’d collected the samples incorrectly, but I wouldn’t have to admit it to everyone.

Andrea nodded with understanding. She knew how difficult it would have been for me to admit my mistake and convene another clinic.

“Why don’t you come here after work tomorrow? You can take blood from me and I’ll show you how to put it into the sample tube without hemolyzing it. There are lots of tests it can affect.”

“You’re on,” I said. “Thanks so much.”

The next day, I drove up to the hospital after work. Andrea bravely bared her arm and I took blood from her. Then she showed me how to carefully let the blood flow into the tube. It was such a simple correction, and I’d managed to work in this field for years without knowing about it. It made me think there might be many other mistakes waiting for me.

“I hate making mistakes,” I said to Andrea.

“Yeah. It’s called being human. You can fix this one, though. Just don’t use much pressure.”

“No fear of that.”

I’d escaped public humiliation by pure luck. As a lesson in lab technique, it was unforgettable.

Excerpt from ‘Always On Call: Adventures in Nursing, Ranching, and Rural Living,’ copyright 2024 by Marion McKinnon Crook. Reprinted by permission of Heritage House. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: