In the opening scene of the new documentary Copa 71, retired American soccer superstar Brandi Chastain is asked what year the first Women’s World Cup took place. Without hesitation, she responds: “1991.”

There’s a pause, and then off-screen the filmmaker says, “I’ve actually got something that I’d quite like you to watch.”

What’s revealed is remarkable footage of young women charging a soccer pitch in front of hundreds of thousands of roaring fans. Turns out that Copa 71, the first Women’s World Cup, took place in 1971 in Mexico City. It was the largest event in the history of women’s sport, drawing an estimated crowd of more than 110,000 people.

Chastain’s reaction — bafflement, shock and fury that this piece of history has been entirely excised from the annals of sports — echoes the main thrust of the story. How the heck did this happen? And how did no one really know about it until now?

In systemic fashion, co-directors James Erskine and Rachel Ramsay set about recreating not only the history of Copa 71 itself, but also the greater cultural moment when women playing soccer was alternately viewed as either a joke or a threat. Or both.

The task of laying out the topsy-turvy story of women’s soccer falls to historian David Goldblatt, whose deadpan manner and acerbic delivery are very funny, if a tad depressing.

In the United Kingdom, the popularity of women’s teams often attracted larger crowds than men’s matches, but this did not stop the governing body of the Football Association from asserting that playing soccer might prove harmful to women’s reproductive organs. I guess all that running and kicking might make uteruses fall out or something.

But, as Goldblatt explains, the real root of the ban was power and money, as the women’s matches did not fall under the direct control of the FA and attracted large, enthusiastic crowds that rivalled those of the men’s teams.

The United Kingdom was not alone in blocking access to the game from the 1920s onwards. Both France and Germany enacted similar public relations campaigns maintaining that soccer was hazardous to women, while Brazil declared the sport illegal for female players.

In this atmosphere, women still managed to find ways to kick a ball about.

The only girl in the world

Italian team captain Elena Schiavo explains in the film that when the neighbourhood boys tried to stop her from playing when she was kid, she simply beat them up. Members of the other teams included in the World Cup tell similar stories of humiliation or worse.

Silvia Zaragoza from the Mexico national team was forced to play in secret when her father threatened her with violence if he caught her playing. As she states in the film, she came of age thinking she was the only girl in the world desperate to play her chosen sport.

Other women, like Carol Wilson, who captained the English team, came to soccer a bit later in life. After being raised on Newcastle FC games, Wilson started competing when she joined the Royal Air Force and witnessed women playing for the first time in her life.

Although another women’s soccer event had taken place in Italy the year prior, the event in Mexico City, organized by the Federation of Independent European Female Football, or FIEFF, was able to make use of the facilities and infrastructure that had been put in place for the 1970 men’s World Cup.

But Copa 71 did not begin as a feminist hurrah. Just the opposite, in fact.

The success of the men’s World Cup in the year prior convinced promoters that there was money to be made in the international tournaments, and the idea of a women’s event was vigorously promoted.

The mascot for the event, a wasp-waisted cutie-pie, was named after the goddess Xochitl. Sponsored by Martini & Rossi, the matches initially attempted to capitalize on femininity, with goalposts painted pink and a marketing campaign that promoted the games as an opportunity for men to ogle women in shorts.

With FIFA putting the kibosh on the women’s games happening in smaller stadiums, the two largest arenas in Mexico were the only venues available. In addition to the massive Azteca stadium in Mexico City, the Jalisco stadium in Guadalajara was put into service to host the women’s matches.

A total of six international teams from Italy, France, Denmark, England, Mexico and Argentina were assembled, and it was game time.

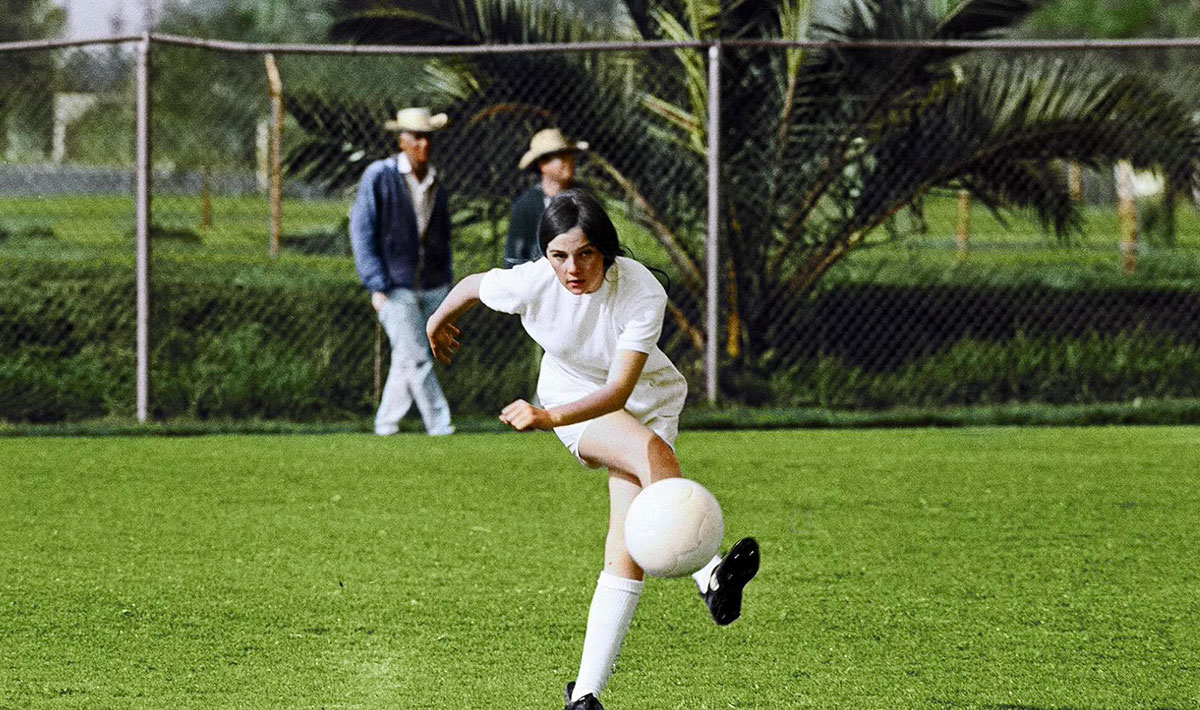

When the women finally took the field, all the silly frilliness fell away. These were warriors: tough, battle-tested and ferociously competitive.

The accumulated roar of 110,000 people in the Azteca stadium still stuns the women after so many years. The flood of memories shared freely provides one of the film’s primary pleasures as team members recall their first experiences of playing on the world stage.

In with a bang, out with a whimper

Many of the women were still in their teens, including Denmark’s Susanne Augustesen, 15, Gill Sayell, 13, and Chris Lockwood, 15, under the leadership of 19-year-old captain Carol Wilson. Most had never been on an airplane or even away from home.

As Wilson recalls, when the English team arrived in Mexico City, they were greeted by huge crowds lining the streets who threw gifts and toys into the window of the British team’s bus. Even many decades later, Wilson still seems gobsmacked by the experience. In addition to the games themselves, the different teams were feted like superstars with parties, events and swarms of fans following their every move.

In the opening game of the tournament, Mexico and Argentina duked it out in front of a massive crowd. Despite some questionable officiating, Copa 71 was a roaring success.

The huge attendance and media frenzy did not preclude some additional complexities from popping up. After defeating Italy in the semifinals, the Mexico national team was poised to play against Denmark in the final.

But it was reported that the women might not play, since none of the team members had been paid, despite the organizers and sponsors making considerable profits. With increasing pressure, the women dropped their request for recompense and the final match went ahead.

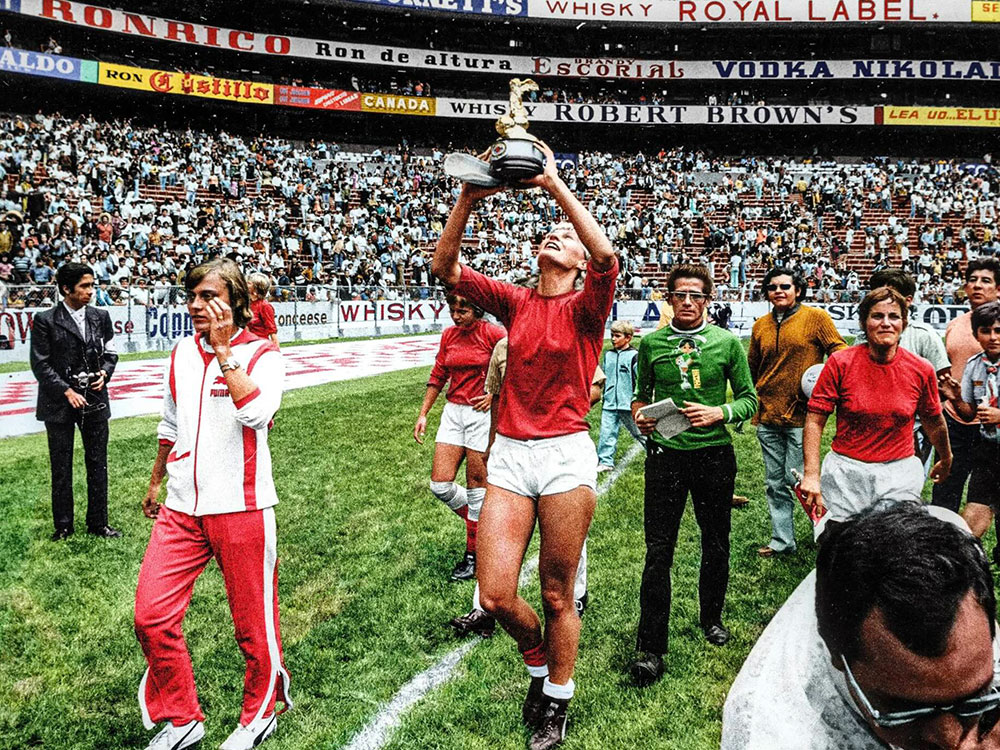

After Denmark won 3-0, members of the defeated team from Mexico remember the entire stadium of 110,000 people sitting still and silent. The silence and tears didn’t last, however. Within moments the entire stadium was on its feet, applauding and cheering.

After returning home, expecting some fanfare, the U.K. team was greeted by crickets at the airport, without even a single photographer on site. As Wilson says, “There wasn’t even the one guy and his dog who turned up to watch us play on Sundays.”

And as if this weren’t bleak enough, the women’s team discovered they’d been banned from playing. Team captain Wilson quit soccer after being humiliated onstage by male soccer administrators at a dinner event for the Newcastle United Football Club. She didn’t speak to her teammates for more than 50 years.

The winning team from Denmark was treated only slightly better. As players Birte Kjems and Ann Stengard recall, there was a party and plenty of media attention, but after that, nothing.

They were expected to go back to their regular lives and forget about soccer. As Stengard says, “I was so naive, I thought we could go on from the spot that we were and build up, but the men said, ‘Uh, no, no, there’s been enough publicity about women.’”

Sidelined, but not erased

Despite the success of Copa 71, the pressure exerted by FIFA on the Mexican Football Federation resulted in the organization abandoning the women’s national team.

With arenas threatened with fines or bans if they allowed women to use their facilities, women’s soccer entered a dark age that lasted for decades. Even after the bans were lifted, the lack of infrastructure and support kept female players on the sidelines.

As David Goldblatt sums it up: “And thus women’s football, despite the incredible energies of the era, was crushed.”

Except that it wasn’t.

The first official FIFA Women’s World Cup took place in 1991 and cemented the fame and skill of the teams featured, including Chastain’s famous moment when she ripped off her jersey after scoring a winning penalty shot in the 1999 Women’s World Cup final. As the film emphatically states, women’s soccer is currently the fastest-growing sport in the world.

But despite recent successes, a lot of the old crap hasn’t really gone away.

Soccer is certainly not alone in treating female athletes worse than their male counterparts, whether in money, attention or simple respect.

The recent furor over American basketball phenomenon Caitlin Clark is a case in point.

From insults about her physical appearance to allegations of her success stoking racial divisiveness and cat fights in the Women’s National Basketball Association, it’s the same old story.

Despite greater acceptance, women are still fighting many of the same battles as their mothers and grandmothers.

But one thing is clear from Copa 71. Whatever the forces aligned against them, women will never stop fighting for freedom, equality and the opportunity to do the things they love. The love of the game, be it soccer, basketball or hockey, is determined not by sex or gender but by passion and grit. Qualities that women have always possessed.

‘Copa 71’ is available to screen via various streaming services on June 25. ![]()

Read more: Gender + Sexuality, Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: