On a fair-weather day, the summit of Mount Everett is a great spot for fellow travellers with mud-caked boots and excitable dogs to rest from their climb and enjoy the view. Today, a cloudy Sunday, I can’t see much of anything. I can, however, hear the lively hum of wildlife through the quiet.

Damian Assadi, chair of the Everett Crowley Park Committee and a natural resource conservation student at the University of British Columbia, has taken his morning off to give me a tour of the park. Here at the summit, he takes a moment to show off one of the committee’s “stewardship areas” and the extensive, meticulous work the committee has done on it.

“It doesn’t really look like that much right now,” he says, but until fairly recently, there used to be dense bushes of Himalayan blackberry and other invasive species unfurled across this stocky, steep hill.

Native plants have just been planted to replace the thorny mesh, Assadi says. Over the last two years, they’ve put about 2,000 volunteer hours into the park.

“That’s where the Everett Crowley Park Committee comes from — the fact that the community became so invested in this park and wanting to see it stewarded and wanting to see it be an urban wilderness rather than being residential housing, rather than being a golf course, rather than being a hang-glider station,” Assadi says. “The community fought for this park.”

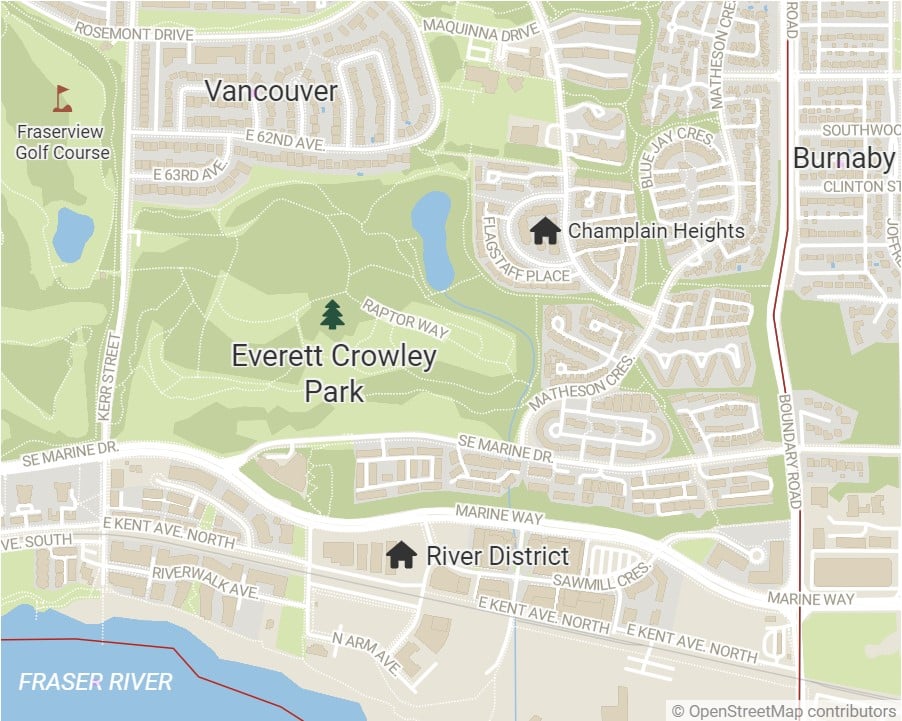

From the summit, Assadi orients me to my surroundings and the park’s boundaries — obscured by a dense, encircling tree line is Marine Drive, a major city thoroughfare.

This brambly mountain in Vancouver’s fifth-largest park might seem at odds with its rapidly developing surroundings, particularly the River District neighbourhood to its south.

Even more surprising: beneath the fresh layer of mud beneath our feet, and further below the heaps of dirt, stone shavings and wood chips, there is a generation’s worth of garbage and waste. Before it opened to the public in 1987, Everett Crowley Park was Vancouver’s official town dump for over 20 years.

Entangled in this story of life growing out of garbage is the story of Everett Crowley, a man who found his way in a political establishment that didn’t always know what to make of him.

From this mountain, even on a cloudy day, you can see Vancouver growing into itself.

Before the dump

Just south of where the park sits now, according to a 1997 pamphlet produced by the Evergreen Foundation, there was a Musqueam village called Tsukhulehmulth on the north arm of the Fraser River.

This place was used for fishing, hunting and gathering pre-colonization, Assadi says.

Vivian Creek, which flows through the nearby Fraserview Golf Course, and Kinross Creek, which flowed through a ravine that once cracked open the park’s current area, were key resources for the village.

By 1888, what is now the park was owned in large part by the family of William Henry Rowling, a corporal in the Royal Engineers.

The lots comprising the park became part of the municipality of South Vancouver when it was established in 1889. In 1929, South Vancouver amalgamated with the City of Vancouver.

Eventually the lots that formed what is now the park “reverted to government control,” according to the pamphlet.

The story of the site’s misadventures as a landfill begins just over 10 kilometres to the northwest, as the City of Vancouver began seeking alternative solutions for the “long-standing nuisance” of the False Creek garbage dump.

Citing “hot-weather complaints about odours” from that dump, a Vancouver Sun article from July 25, 1946, notes that for about a year the city had already begun making use of “a large gully in the south-eastern portion of the city.” This new dump near Kerr and 63rd Street, it reads, was a “sparsely settled area of the city with no houses near.”

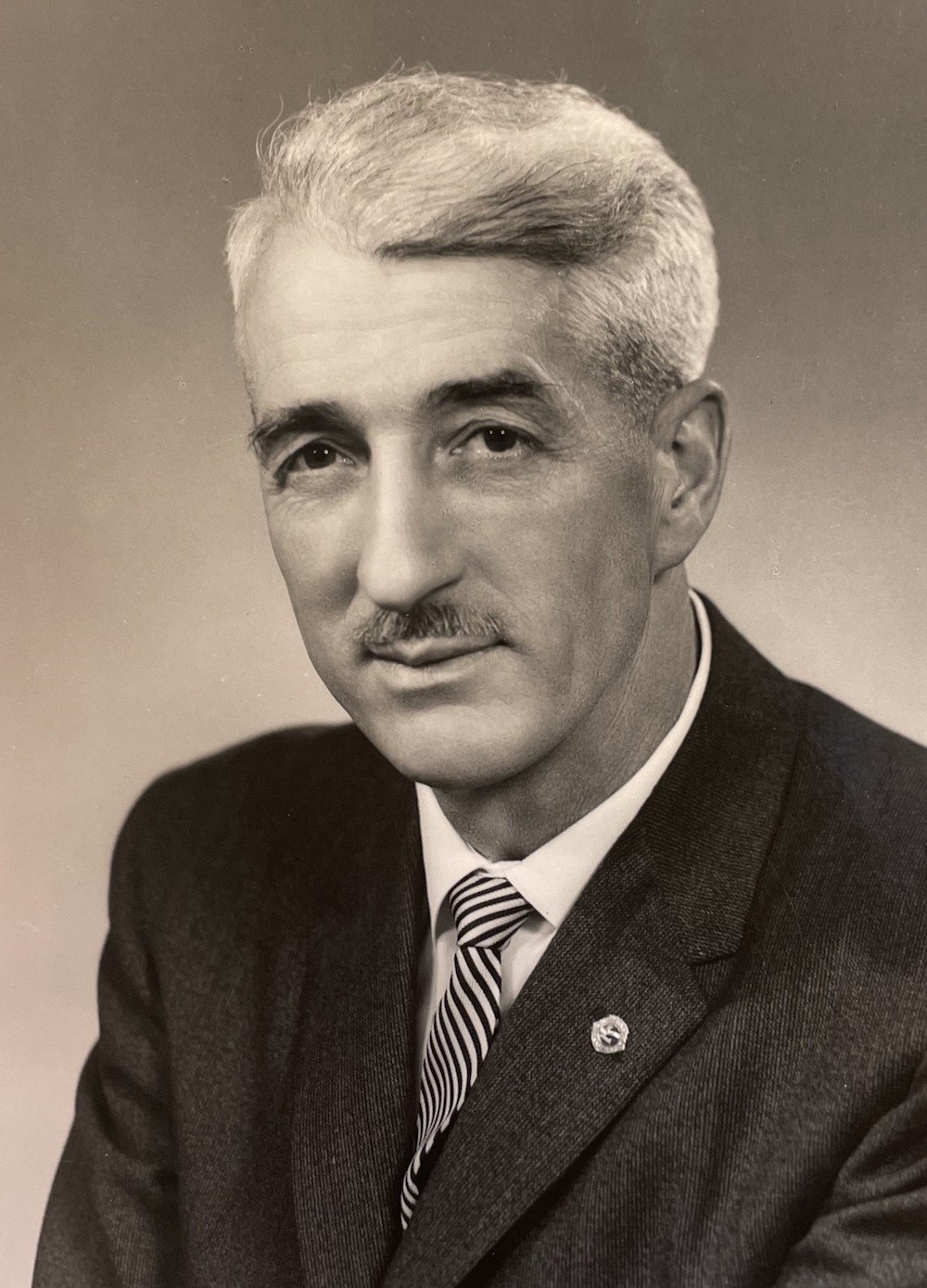

That same year, 1946, Everett Crowley began shaking up Vancouver’s local political scene. He’d refused to pay a $5 poll tax, levied to resident men who did not own property. Then in his late 30s, Crowley was the former president of the Junior Trade Board and manager of his family’s business, Avalon Dairy, one of the oldest dairies in B.C.

The dairy operated out of a farmhouse on Wales Street just a 12-minute bike ride north from the new dump site (it is now a multi-unit residential building).

City authorities had no clue what to do about Crowley, according to an article in the Aug. 28, 1947, issue of the Vancouver Sun.

By then, he’d paid the $5 fine for not paying his 1946 tax — he didn’t want to appear “pig-headed” — but still had not paid the actual tax. He’d rather go to jail, he said.

When he was eventually sentenced to three days in jail, he told the Province on Sept. 4, “They have no other alternative now, and I hope they’ll come for me this afternoon.”

He was “arrested” at his home that evening and walked into police headquarters — wearing a “grey Homburg hat at a jaunty angle” and “a well-pressed grey suit” — distributing copies of a statement demanding council get rid of the poll tax, so he could then “go after the provincial government to have the poll tax act abolished,” according to the Sun.

Crowley was released on Sept. 6 after spending 44 hours between city police headquarters and a cell at Oakalla Prison Farm.

By then, his time in jail had become a bit of a sideshow. According to a Sept. 8 Vancouver Sun story, the Friday night while he was in Oakalla, “a prowler equipped with wire snippers and a drill tried to burglarize the Crowley home.”

One of his children, a five-year-old boy, woke up in the middle of the night to the sound of someone trying to break in. When Jean Crowley, Everett’s wife, tried to call the police, she found that the home’s phone lines were cut. Her neighbour’s phone wires had also been cut.

That same neighbour was eventually able to call the police from a phone across the street.

The next year, after being summoned yet again for not paying his poll tax, and after some legal back and forth with the city, Crowley paid the tax and court costs to avoid a contempt of court charge from a second offence.

“They have me cornered,” he told the Vancouver Sun.

Crowley also decided to run for city council in 1948 — to abolish the poll tax.

He did not win a seat that election. But the newly elected city council voted to stop collecting the tax in April 1949, calling it “unfair and inequitable.”

B.C. followed suit in its municipal act of 1957.

On both counts, Crowley was no doubt thrilled.

The rise of a civic power couple

But Vancouver hadn’t seen the last of the Crowleys. Everett Crowley ran again to become an independent alderman in municipal elections of 1949, 1951 and 1953, all of which he lost.

Two years later, Jean Crowley decided to run for a school board seat as an NPA candidate. She won 46,865 votes and became a school board trustee in 1955.

She ran again in 1957. This time, she campaigned so hard that she spent election day in bed with the flu, only getting out of bed to go vote, according to her husband.

She won re-election with 72,778 votes, considered then the “heaviest support of any candidate for civic office in Vancouver’s history,” according to a Dec. 12, 1957, issue of the Province. She became deputy chair of the school board.

In 1959, she won 38,968 votes, the most in that election, and was elected chair of the school board.

Everett Crowley eventually received an NPA endorsement when he ran for park board in 1961 and was a park board commissioner from 1961 to 1966.

Vancouver’s own perennial troublemaker had finally become a civic politician.

A stench ‘worse than a week-old battlefield’

Meanwhile, what is now Everett Crowley Park had become the city dump. And as it turns out, it’s really hard to manage garbage for an entire city.

In the 1950s, citizens complained it was crawling with rats. One man who lived nearby told a journalist from the Province that he’d once been in the habit of killing three or four rats a day in his garden “before the health department started poisoning them.”

Alderman Halford Wilson told the Province that the “stench from the dump was worse than a week-old battlefield.”

After quoting a recent report from the sanitary inspector recommending “immediate action,” council requested commissioner of works John Oliver investigate the complaints.

It is here that we start to get a glimpse of what this place would become. Oliver told council at that meeting that the dump was already nearly full. For some months now, he said, the city had been looking for a new solution for its garbage needs and planned to turn the current dump into parkland.

But a year later, problems persisted. After the city extended the dump’s boundaries, a group of Southeast Marine Drive residents told the Province they were considering an injunction to close the dump if the city did not address their complaints.

The back and forth about legal actions, stench, dump extensions and potential park conversions extended for years, punctuated by a 1966 labour strike that caused a “garbage emergency.” As soon as the strike was quelled, a “spontaneous combustion” sparked an underground fire that burned uncontrollably for two months, according to the 1997 Evergreen Foundation pamphlet.

Finally, in 1967 — nearly a decade after the city first admitted the dump was full — it was shuttered for good.

The long twilight of the Kerr Road Dump

By this time, Crowley had spent over half a decade in city politics. In 1968, he ran for council one last time. Though he initially won, spending some time as a councillor, a subsequent recount showed that he’d actually lost by a margin of 32 votes.

But he remained politically engaged: Crowley was on the Vancouver City Planning Commission from 1969 to 1976 and was chair of the commission from 1972 to 1974.

A little ways away from Crowley’s family dairy, the former dump that was to become his namesake was sitting empty, still a neighbourhood nuisance — it had become a popular spot for motorcyclists.

In 1974, city council unanimously carried a motion to turn the site “over to the care and custody and maintenance of the Park Board.”

But, as former park board commissioner Bill McCreery told The Tyee, “you can’t just have a garbage dump and suddenly, overnight, it becomes a park.”

In the 1970s, the city earmarked the neighbourhood containing the dump, known today as Champlain Heights, to have a mixture of different types of housing as well as a lot of parks, according to McCreery. Residents of the city’s east side often felt that the city favoured the west side when it came to parks and other civic facilities, McCreery remembers.

The dump became a park, McCreery told The Tyee, “because it wasn’t really useful for anything else.”

“It’s basically not capable land to put structures on, because of the depths of the garbage that’s on that site,” he said.

After the park board approved a motion to turn the old dump into a park, McCreery says, it took some time to perform the remediation work that was necessary.

“You get things like methane and so on which can be created by rotting garbage and that can be not just toxic, but it is also explosive,” McCreery said. “I think there was some drilling that had to be done to put pipes down to make sure there weren’t gases trapped underneath the soil.”

The approval for a park also initiated work to put on “a fairly thick layer of fill on that site,” from construction sites in the city “over a period of years.” At the time, this was an alternative to “trucking it out and putting it on a barge and dumping it in the middle of the Salish Sea.”

It wasn’t easy sailing. But nature soon began to pitch in.

Silvia Hagen, a volunteer on the Everett Crowley Park Committee, has lived in the neighbourhood since the late 1970s.

Her father, Manfred — “Manfred’s meadow,” within the park, is named after him — worked at the MacMillan Bloedel sawmill that lay on the Fraser lands, along the north arm of the Fraser River.

By the late ’70s, Hagen says, the landfill had been closed and capped. But even as it sat empty and fallow, it was still being called “the dump.” And people were definitely still illegally dumping their garbage, she says.

“There were old cars dumped there in the ravine, and you would see the hood of the car still sticking up. It had started to get absorbed into the ground. And then you would just see the front of the car, and then just the headlight or the bumper, and then eventually it was gone.”

The park’s topography is testament to this legacy, Hagen explains. As the garbage underneath decomposed at varying rates, it led to hilly undulations.

Towards the centre and east of the park, there are places where the snow melts faster than in other sections. This is due to the steam vents produced by decaying garbage underneath releasing heat, she says. Like a tropical microclimate, right in that section of the park.

The Everett Crowley moniker

So just how did this decades-long restoration project come to bear the name of Vancouver’s poll tax martyr?

When the time came to give the park a name, ideas were floated by park board staff and by community groups like the Champlain Heights Association and its subcommittee, the Kerr Road Park Committee, which had advocated for the park for years.

Possible names included Kinross Park, in honour of the now-gone stream, and Townley Park, per park board staff recommendation.

It was former park board commissioner Christopher Richardson who proposed that it bear the name of Everett Crowley, who had passed away just three years before.

With Avalon Dairy’s location in southeast Vancouver, and the Crowleys’ active community engagement over the years, the family had been “a strong force” in the neighbourhood for a long time, Richardson says.

When Richardson asked Jean Crowley if they could use the family name for the park, she was thrilled about the idea, he says. The motion to rename the Kerr Street site to Everett Crowley Park was carried unanimously.

Before the park’s dedication on June 27, 1987, Richardson stopped by Avalon Dairy. He walked into the park with an idea on his mind — and a six-bottle crate of milk in his hands.

On a raised wooden observation structure on the northeast corner of the park, near Avalon Pond, close to where the Champlain Heights Community Centre stands now, dedication attendees toasted with milk, rather than the customary champagne. Unfortunately, Richardson couldn’t participate fully — he’s allergic to milk.

From dump to biodiversity

The park’s previous life as a dump led to lively hijinks on walking tours led by Kevin Bell, a member of the Vancouver Natural History Society, Richardson says.

“On a cool crisp foggy morning, we’d be traipsing through the park, and he would be talking about the history of the park, and then what he would do is he would bring out a cigarette, which he didn’t smoke,” Richardson says. “And then he’d flick the cigarettes at an opportune time.”

Because of the “digestion” of organic materials from its previous life as a dump, “all of a sudden, this big, honking flame would ball up at your feet. And then he’d say, ‘Oh, oh, I guess garbage dumps vent methane as a byproduct. And oh, that’s a good time to talk about the garbage stuff.’”

Looking at a map, Assadi says, tree cover and vegetation make it obvious that this area is now one of the greenest places in the city.

Most of the larger, more established trees across Everett Crowley Park tend to be “pioneer species” like red alder and black cottonwood. These species are the first plants that grow on a site after “a disturbance” like logging or, in this case, a landfill, Assadi says.

In some of the park’s stewardship areas, the trees are just a bit taller than a person.

Other areas “aren’t exactly prime real estate for stewardship work because of its history,” Assadi says. One spot, where the fill is quite “stony,” will become a wildflower area.

Committee volunteers have recently planted red elderberries, red flowering currants, snowberries, Nootka roses and thimbleberries.

And lots of Douglas fir — it’s a tree that’s dominant in our “biogeoclimatic zone” and one that is likely to be tolerant of climate change, even as biogeoclimatic zones shift.

But another native species that we see in this park is not going to do well in the changing climate — the western red cedar, also known by Coast Salish peoples as the “tree of life.”

“Our restoration plants have to account for the fact of climate change and that the ecosystems that are going to be here are not going to be the same ecosystems that have thrived in the past,” Assadi says.

The committee is also actively fighting “a pretty big battle” against invasive species like morning glory, English ivy, English holly and giant knotweed.

“We have organizations that are dedicated to invasive species that come into this park to give their staff a tour, as it is such a great example of how many invasives that you can find in Vancouver,” Assadi says.

Assadi and I eventually make our way to the easternmost corner of the park, to Avalon Pond — the site of a former quarry.

While the pond wasn’t part of the landfill, there was a bit of leaching from it, Assadi says. With all the rock being extracted from the site, it naturally filled up with groundwater, water that would have been directed towards streams like Kinross Creek.

In the water there are cattails and three-spined stickleback, native species like salmonberry, red cedar, red alder and Pacific willow, and dragonflies.

Amphibians like the tiny Pacific tree frog used to be quite common in this area, Assadi says. There was once a time when you could hear hundreds of them chorusing into the evening.

“We just don’t find the Pacific tree frog anymore,” Assadi says. His guess is they’ve been outrun by palm-sized invasive green frogs in the pond.

“I’m holding on to hope now that there could be some that are out there that we just haven’t found.”

The committee hasn’t had the connections or the funding to do the number of biodiversity surveys they conducted in the 1990s and 2000s, Assadi says. But they’ve recently acquired tens of thousands more in new funding that will let them expand their operations and has even let them hire a part-time contractor.

And they have received some good news too.

Over the last year, while doing egg surveys and adult amphibian surveys in the pond, the committee has confirmed the presence of egg masses not belonging to the invasive green frog.

Initially, they theorized it was the northwestern salamander, but they couldn’t be sure.

Then, last summer, as Assadi and Hagen led a nature walk through the park, something remarkable happened. As Assadi talked about the pond, Hagen was pulling weeds from underneath a sign that said, “No dogs allowed in the pond.”

Assadi heard her gasp. She called, “Damian, come look at this.”

When Assadi got closer, he gasped too. At their feet was an adult northwestern salamander.

“That sighting is our first documented sighting of a native species in probably the last 20 years,” Assadi says. ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: