At the Vancouver Aquarium, the call of the pleasing poison frogs (Ameerega bassleri) pierces the air. It takes a moment to realize that such a big sound is emanating from such a diminutive creature — the frogs are about the size of a quarter. The male’s sides are heaving, like a miniature bellows, issuing a trilling song that cuts through even the thick glass of the tank that houses the little guy and his buddies.

The human fascination with frogs is ancient stuff. I’ve loved them since I was a child, spending endless hours watching the action in the pond on our family farm on Kootenay Lake. There is something deeply compelling about frogs: the fragility of their small bodies, round little bellies, skinny arms and legs. The curious equanimity of their expressions. Almost every culture on the planet includes frogs in mythology and ancient tales. Ancient Egyptians, Romans and Greeks worshipped frogs as fertility symbols, with a little bit of licentiousness thrown in to spice things up a bit. But things have not been easy for our amphibian friends.

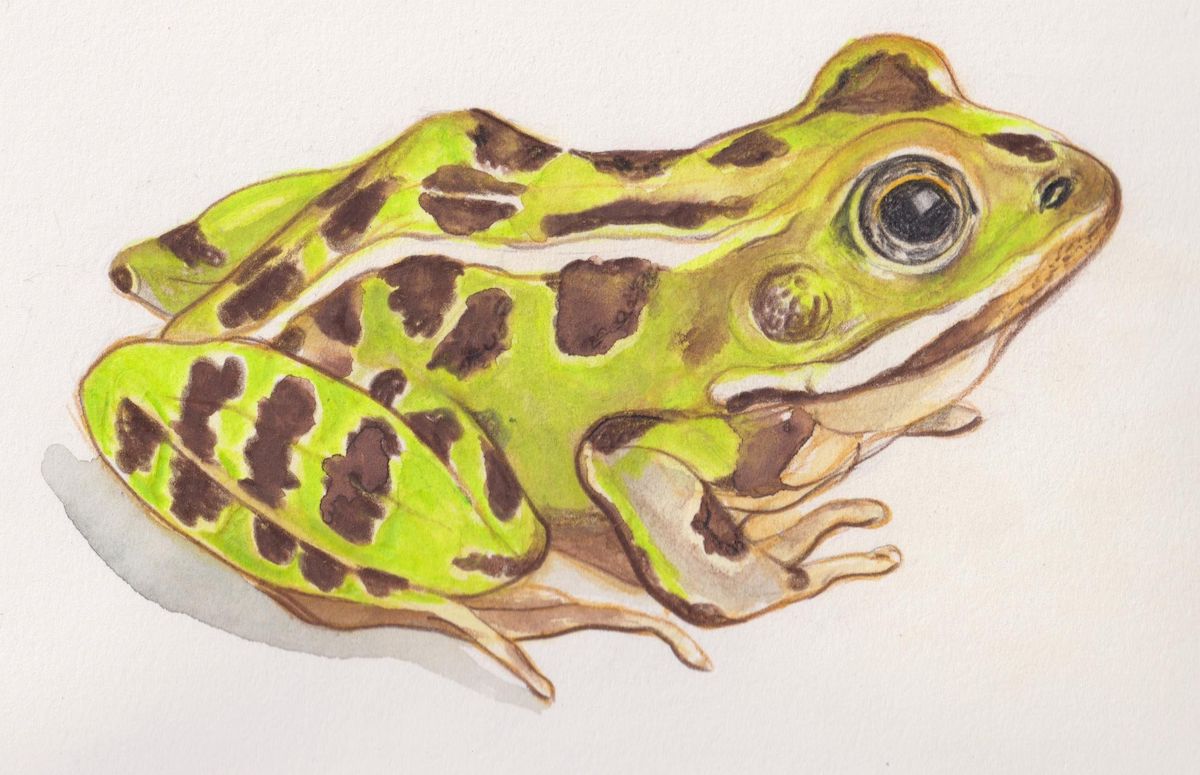

The global drop in frog populations is hitting hard in B.C. The northern leopard frog, native to the Creston Valley, has seen its numbers fall. According to studies undertaken by the provincial government, “This species declined in British Columbia in the late 1970s, and by the mid-1990s was only known to occur near the town of Creston, south of Kootenay Lake.”

The northern leopard frog was placed on the provincial Red List and considered locally extinct in the wild. One of the last remaining habitats for the critically endangered leopards is the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area in the Kootenays.

I grew up watching these frogs before their populations suffered a catastrophic collapse in the 1980s and ’90s. But they have rebounded in recent years. Part of the solution: the horny frog program at the Vancouver Aquarium. I’m not kidding!

Despite their seeming fragility, frogs have been around since the age of the dinosaurs. These little guys are tougher than they look. Frogs, salamanders and toads belong to the caecilian family. In the Vancouver Aquarium’s Frogs Forever section, more than 20 different varieties survey the world from leafy green tanks, unperturbed by the threats that are currently decimating their populations around the globe. The combined exhibition and research program is dedicated to the preservation and benefit of frogs.

On the roof of the aquarium in Vancouver’s Stanley Park is a huddle of greenhouse sheds where a rigorous frog breeding program takes place. At the height of breeding season, the place smells like a gym locker room, such is the level of pheromones in the air, according to Frogs Forever staff Andrew Cumming. The greenhouses house our two local frog species. In addition to northern leopard frogs, the aquarium also breeds Oregon spotted frogs (Rana pretiosa, meaning “precious frog”).

The Vancouver Aquarium has taken something of a leadership role in trying to re-establish endangered frogs in the wild. Beginning in 2001, the breeding program released up to 25,000 leopard frog tadpoles in the Kootenays. The frogs that are currently housed in the aquarium represent a kind of insurance plan in case things do not go well.

Cumming and his colleagues at the Vancouver Aquarium are part of a global initiative to support and stabilize healthy frog populations around the world, beginning with its breeding program.

As Cumming explains, it is the job of a certain person, sitting in an office somewhere, to determine the sex lives of frogs. They judiciously decide which specimens are the most fit to get it on and which must sit sadly on the sidelines, clutching their dance card to their chest.

From tomato shapes to old-man bagginess

The size and variation of the frogs that call the Vancouver Aquarium home are a little surprising. Although I suppose they shouldn’t be, since frogs hail from every corner of the planet, from the lushest jungles to the most remote alpine lakes, and all over British Columbia.

This diversity of habitat is matched by a wondrous plethora of frog shapes, sizes and colours, from the tomato-shaped expanse of the false tomato frog (Dyscophus guineti) to the old-man bagginess of the Titicaca water frog (Telmatobius culeus).

Titacaca make their home in a cold-water lake that straddles the border between Bolivia and Peru. Their appearance has evolved to make the most use of the region’s oxygen levels, hence the looseness of their skin and rather startled expressions.

Weird, wonderful frog behaviour is as fascinating as how they look. The Amazon milk frogs (Trachycephalus resinifictrix) are so named for their habit of secreting a milky blue substance that would make any other creature threatening them go “Ewww.” It ain’t pretty, but it works.

The Amazonian horned frog (Ceratophrys cornuta) is dubbed the “Pacman frog” because of its wide mouth.

These adorable little guys are poisonous

Cuteness has not always been a good thing for our froggy friends, as humans immediately want to pick them up and mess with them.

To combat their fundamental, thin-skinned vulnerability, frogs have developed many methods of survival.

The most poisonous members of the frog family often possess the most vivid coloration. The hues are extraordinary. As its name indicates, the golden poison frog is as brightly coloured as an incandescent light bulb. Candy-coloured as they may be, don’t pop them in your mouth unless you fancy a quick trip to the great beyond: their vibrant yellow skin denotes their level of toxicity to would-be predators.

These little guys (they’re two to three centimetres long, on average) are actually among the most poisonous animals on the planet, containing enough toxins to take out 10 adult humans.

As Cumming says, this level of toxicity makes the golden poison frog somewhat belligerent, thuggish even. When he has any work to do in their tank, he explains, he often shoos them away as they fearlessly investigate whatever is happening.

Still, the golden poison frog’s toxin levels tend to dissipate in captivity, says Cumming, as a large part of the poisonous stuff comes from a frog’s diet in the wild.

Of the more than 170 species of poison frogs, not all sport acid-bright colours. Many are mottled, bottle green or deepest shining navy. Spotted, striped, like a decorator gone mad, they don’t even look real.

One of the most richly designed is the aforementioned pleasing poison frog, which belongs to the poison dart frog group. These frogs were previously known as poison arrow frogs; Indigenous people in South America used them to add killing power to their blow darts.

Vibrant, but not deadly

Even looking toxic is enough to scare off predators. The mimic poison frogs (Ranitomeya imitator) are as vibrant as their more poisonous fellows, but without the deadly edge.

One of the most dangerous creatures in the facility is a dirt-brown colour, a thoroughly unremarkable looking animal. At more than 40 years of age, the rough-skinned newt is also one of the oldest inhabitants. As Cumming says, the old guy has been an inhabitant of the aquarium for many decades, after he was discovered living in Stanley Park.

“I would only add that he is, at a minimum, 42 years old. Obviously, he wasn’t zero years old when he was collected and there is no way of knowing precisely how old he was at the time, so he could be a bit older,” Cumming says. “In any case, he is old enough to have witnessed a pre-Expo 86 Vancouver!”

Like a crotchety old man, the newt lurks at the back of his tank, with the same expression and demeanour as a neighbourhood crank. Listen closely and you can almost hear him say, “Get away from my tank, you damn pesky kids.”

It’s not an unwarranted reaction. On a busy afternoon at the Vancouver Aquarium, it strikes me that humans are an unbelievably noisy species. We talk all the damn time, at the top of our lungs. It’s little wonder that many of the inhabitants of the frog section of the aquarium are tucked away in the farthest corner of their environs, seemingly hiding from the human audio onslaught. I would do the same if I were in their situation.

Combating mass extinction

It’s grim out there. More than half of the world’s current amphibians are under threat. Their disappearance is an incalculable loss to the planet, but also to the many frog lovers around the world.

In addition to loss of habitat, invasive toads and hungry humans, a parasitic fungus called chytrid has taken a heavy toll on frogs. To combat the single largest mass extinction since dinosaurs vanished from the planet, aquariums around the world have collaborated to create robust breeding programs, including one in the Fraser Valley.

Another species most under threat is the Oregon spotted frog. The aquarium joined forces with a variety of other organizations to help support the current populations, as well as supplement their numbers, aimed at reintroducing the species into the wild. Since 2007, the program has grown exponentially, with 3,000 tadpoles and youngsters released in Fraser Valley wetlands.

The mind-boggling range of colours and forms that these diminutive creatures encompass is yet another reminder of the almost ridiculous level of complexity of the natural world.

They are wondrous, extraordinary little beings. So beautiful, adaptable and tenacious, hanging in there despite the many predations and threats to their continuance. How can you not love them? ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: