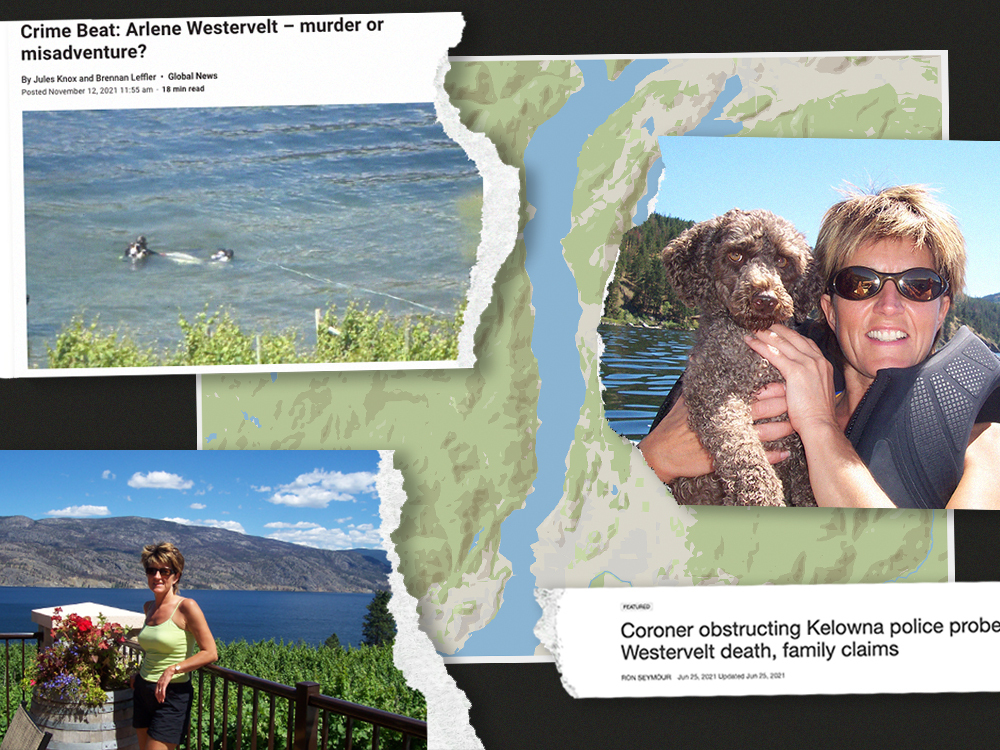

It was warm and sunny on June 26, 2016, when Arlene Westervelt and her husband, Bert, headed out on Okanagan Lake in their canoe.

The water was calm. The couple were experienced boaters who had taken their canoe on multi-day trips in Canada and the United States. They lived in Lake Country north of Kelowna and knew the lake well. Arlene, 56, was a marathon runner and, her family says, a strong swimmer.

But Arlene never made it back from that canoe trip. Other boaters saw the canoe suddenly flip. Bert would later tell police he and his wife were not wearing their life jackets and the boat had capsized when Arlene reached for her water bottle. He would later say Arlene had slipped under the water after he moved her foot off the canoe; he had then tried to grab her arm, but she had pulled out of his grip.

Her body was recovered the next day.

And the actions of police and the BC Coroners Service in the week that followed Arlene’s death have been under intense scrutiny ever since.

In news reports and a response to a civil lawsuit, Bert Westervelt has said his wife’s death was an accident.

He was charged with second-degree murder in 2019, but those charges were stayed in 2020. No evidence about what happened that day has ever been heard in court. The Tyee contacted his lawyers for comment for this story but did not hear back. In 2021, he told CTV News Arlene’s death was a tragedy and that he missed her. “The charges were dropped because I did not commit any crime,” he said.

But from the time she first heard her sister was missing, Debbie Hennig believed Westervelt had killed Arlene. She and other family members repeatedly called the RCMP to report their suspicions, Hennig said, even before Arlene’s body was recovered.

Despite the family’s concerns, in the days after Arlene’s death neither police nor the coroner treated the case as anything other than a tragic accidental drowning, and her body was not sent for an autopsy.

Hennig said she called police repeatedly to beg officials to do an autopsy; instead, her sister’s body was embalmed in preparation for the funeral.

Then a lawyer came forward with information that Arlene had been preparing to divorce her husband. Police started a criminal investigation and an autopsy was finally conducted nine days after Arlene’s death.

To this day the death of Arlene Westervelt remains shrouded in suspicion and mystery because of the botched investigations.

For Hennig, being left with such serious concerns about how her sister died and why murder charges were dropped has been life-changing, and has led to health problems from the stress and the decision to shut down her business so she could focus on her sister’s case.

“I have dedicated and devoted the last seven and a half years of my life to fighting for justice for Arlene. And I won’t stop until all those responsible are held accountable,” Hennig said.

“They have given me no reason why they shut this down. Prosecutors have just said it doesn’t meet the requirement for a ‘substantial likelihood of conviction.’”

But in order for the charges to be approved in the first place, Hennig noted, there needs to be a substantial likelihood of conviction.

“So how did that change?”

The second-lowest autopsy rate in Canada

The BC Coroners Service has one of the lowest overall autopsy rates in Canada: just 3.2 per cent of deaths in B.C. are sent for autopsy, compared with the national average of 5.5 per cent. Quebec is the only province with a lower rate, at 2.2 per cent.

As The Tyee has reported, when it comes to suspected overdoses, the BC Coroners Service policy of relying on toxicology instead of autopsy makes it an outlier in North America. Just 15 per cent of suspected overdose deaths in B.C. receive autopsies, compared with 60 to 100 per cent in other provinces. B.C.’s policy does not align with recommendations from the National Association of Medical Examiners, which state that autopsies are the most accurate way to determine the cause of death for suspected overdoses.

To forensic pathologists who have been pushing for changes at the BC Coroners Service for years, the Westervelt case is another example of the service not following established death investigation procedures that are common in other provinces.

According to forensic pathologists The Tyee interviewed for this story, in most jurisdictions nearly all drowning deaths are sent for autopsy as a matter of course.

Critics say the Westervelt case is a particularly egregious example of BCCS not operating by established forensic pathology standards and not being adequately guided by doctors with specialized medical training.

“The rule for drowning in a good administration is that there will be an autopsy in all unwitnessed cases,” said Dr. John Butt, a retired forensic pathologist.

“And in a witnessed case, the witness must be impartial — independent from the circumstances.”

Dr. Christopher Milroy, a forensic pathologist based in Ottawa, said autopsies are “standard” for nearly all drowning deaths in Ontario.

The Tyee asked other coroner and medical examiner offices across Canada about their practices for drowning deaths. According to the Alberta medical examiner’s office, “autopsies are performed by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner on the majority of drowning deaths.” The New Brunswick Coroner Services said toxicology and autopsy are conducted on all child drownings, and autopsy is conducted for most adult drownings. The medical examiner services of Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador told The Tyee that autopsies are performed on all drowning deaths.

Lisa Lapointe, who was B.C.’s chief coroner from 2013 until her retirement in January 2024, told The Tyee that Arlene Westervelt’s death investigation did lead to changes and helped to identify “a gap in our policies.” BCCS’s policy was changed in August 2020 to send nearly all drowning deaths for autopsy.

“At the time of Mrs. Westervelt’s death, our policy was autopsy was not mandatory for water-related deaths,” she told The Tyee.

Whether or not to do an autopsy was instead based on “body, scene, circumstances and, as per the coroner’s report, whether that event was witnessed by impartial witnesses,” Lapointe said.

When The Tyee followed up with BCCS to confirm what the service’s policies for drowning deaths were before August 2020, we were told that information is confidential.

As an example of the importance of autopsies for deaths in water, Milroy talked about the murder of four members of the Shafia family — three teenage girls and a 52-year-old woman — who were found submerged in a car in an Ontario canal in 2009. It was only through the autopsies that Milroy discovered evidence that several of the victims had received blows to the head.

“Until you do the autopsy you don’t know what you’re going to find,” Milroy said. “That ended up with four first-degree murder convictions.”

British Columbia has a lay coroner system, meaning that coroners are not required to have medical degrees or training.

That includes the chief coroner. Lapointe is a lawyer, while several previous chief coroners have been police officers. A medical doctor has headed the service just twice in its 45-year history: Dr. William McArthur was chief coroner from 1979 to 1981, while Dr. Diane Rothon headed the service for just nine months in 2010, saying she had to leave because her “professional ethics and personal values are being compromised.”

The current acting chief coroner is John McNamee, a lawyer who previously worked as chief counsel for the BC Coroners Service.

In B.C., field coroners get on-the-job training and can draw on the expertise of forensic pathologists. Some coroners have more specific specializations, such as identification specialists who have training in anthropology and forensic science.

Saskatchewan, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut all use a similar model.

But in several Canadian provinces, medical training is considered necessary for death investigation work. Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador have medical examiner systems; medical examiners must be physicians and are required to have training in pathology. Ontario has a coroner system, but all coroners must be doctors, including the chief coroner.

Lapointe has pushed back against forensic pathologists who have criticized the service. She said the BC Coroners Service has specialized units for areas like domestic violence, child deaths and suspected overdoses, and coroners can also consult with forensic pathologists.

“We’re very comfortable with the level of expertise that our coroners provide in the field,” Lapointe said.

“They go to the scene — we have a very high rate of scene attendance for our reportable deaths.”

Missing evidence for Arlene Westervelt’s family

But for Arlene Westervelt’s family, the damage has been done. Eight years after Arlene’s death in 2016, Hennig has scrupulously documented what she believes were serious missteps by the BC Coroners Service, including delays and reluctance to allow the autopsy to be reviewed by outside experts.

The BC Prosecution Service stayed the charges against Bert Westervelt in July 2020. After a criminal charge is stayed, there is a one-year deadline to restart the same prosecution — something Hennig hoped could happen if new evidence came to light.

The first coroner’s report wasn’t done until Jan. 12, 2021.

It states that the autopsy showed hemorrhages on the muscles of Arlene’s neck and on both eyes. The report goes on to state that “while these hemorrhages can be associated with physical compression of the neck, there were no marks on the skin of the neck, no injury to the hyoid bone and no petechiae in or around the eyes.” Petechiae can be a sign of strangulation.

Drowning could not be “confirmed or ruled out,” wrote the coroner, Lori Moen, who noted that Dr. Jason Doyle, the Vernon pathologist who did the autopsy, found that part of Arlene’s heart was enlarged, which could also point to the possibility that a heart arrhythmia had led to her death.

Moen classified Arlene Westervelt’s death as “undetermined.”

Three months before that coroner’s report was completed, a lawyer for Arlene Westervelt’s family had written to David Eby, who is now B.C.’s premier but at the time was attorney general.

Anthony Oliver asked Eby to allow Ontario forensic pathologist Milroy to complete a peer review of Doyle’s autopsy.

Oliver explained that Milroy is a forensic anatomic pathologist who has done peer reviews for several other medical examiner and coroner services across Canada.

“In suspicious death cases across Canada, the standard procedure is to have a qualified, certified ‘anatomical’ forensic pathologist complete the autopsy and, further, for a second qualified pathologist to review the first pathologist’s findings,” Oliver wrote.

“I understand that in this case, Dr. Doyle is a ‘general’ pathologist, and that peer review may not have been completed.”

Doyle did not respond to a request for comment from The Tyee, and the BC Coroners Service said it would not comment on the letter sent by Oliver to the attorney general. The Tyee also asked the Ministry of Attorney General to comment but did not receive a response.

Hennig also shared email correspondence with The Tyee that showed the RCMP had asked the BC Coroners Service for an external review in March 2021.

“Anthony — I don’t know why someone within the BC Coroner’s Office would claim that an external review was not requested by RCMP — as I have previously communicated, it was requested in March 2021,” RCMP Cpl. Dave Bazett wrote in a July 6, 2021, email to Hennig’s lawyer, Anthony Oliver.

“I can only surmise that the person who said this was not privy to the discussions that have taken place surrounding this issue with the top-level BC Coroner’s Service managers, and/or there is a communication gap on their end. At this time, I am of the understanding that no external review has been authorized by their management, despite us advocating for one.”

Bazett did not respond to a request for comment and a spokesperson for the RCMP said the force could not comment because of an “ongoing court process.”

An external review did happen eventually, but not until August 2022, long after the one-year deadline to restart the stayed prosecution had passed.

That’s when an expert review panel convened by the Ontario Forensic Pathology Service re-examined the autopsy.

Portions of the panel’s report are quoted in a second coroner’s report, dated Feb. 9, 2023. The Tyee asked for the full expert panel report, but the coroners service refused, saying it contained confidential medical information that would be available only to the deceased person’s next of kin.

Hennig says that because Bert Westervelt is considered Arlene’s next of kin, she and her family members haven’t been able to get access to the autopsy report or the expert review panel’s report.

According to the 2023 coroner’s report, the expert panel found that the apparent enlarged heart was likely from “the state of contraction at the time of death and rigor mortis” and was unlikely to have been a factor in the death. That panel was made up of pathologists from across Canada and did not include the pathologist who conducted the initial autopsy or any other employee of the BC Coroners Service.

The panel also found that conducting the autopsy after embalming created problems in determining how Arlene had died. During the embalming process, incisions are made in the neck and groin and chemicals are injected into the body’s arteries to help preserve it.

“The panel agreed that it would have been advantageous if the post-mortem examination had been completed immediately after the death as the delay and the embalming procedure could have compromised signs of drowning and introduced artifacts within the body, including in the soft tissue of the neck,” according to the February 2023 coroner’s report.

“There was no conclusive, positive evidence for neck compression. The findings in the neck and the eyes could even have been caused by drowning or post-mortem artifacts or as a result of embalming artifacts.”

Before the autopsy was completed, the only other examination of Arlene’s body had been done by a coroner. Moen, a former lawyer and real estate agent who has worked as a coroner since 2008, signed the initial coroner’s report. But the coroners service would not confirm whether Moen was the coroner who examined the body or if she was the sole coroner to do the examination.

Hennig objects to the BC Coroners Service having any role in presenting the expert panel’s findings and says its involvement calls into question whether the expert panel was actually impartial.

In response, BCCS says its staff “were not involved in any way in that Ontario review.”

A police investigation plagued with problems

The problems with the BC Coroners Service response aren’t the only clouds over the case.

The actions of Brian Gateley, an RCMP officer who was a friend of Bert Westervelt, also cast doubt on the police investigation. In the days after Arlene’s death — but before the criminal investigation had started — Gateley used RCMP equipment to unlock Arlene’s phone so Bert Westervelt could access its contents.

The RCMP started a code of conduct investigation into Gateley’s actions, and the Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner subsequently disciplined Gateley for sending a letter to Arlene Westervelt’s family in an attempt to explain his actions, despite having been told not to contact them.

The OPCC review decision lays out Gateley’s belief that it was problems with the pathologist’s report, not his actions to unlock the phone, that led to the stay of prosecution, and that he sent the letter in an attempt to explain this to Arlene’s family.

The BC Prosecution Service has never explained why the prosecution was stayed, saying only that the decision “was made by senior Crown Counsel after a careful review of the available evidence.” The prosecution service says the investigation into Arlene’s death remains open.

Hennig and her family hope a civil lawsuit they’ve launched against Bert Westervelt will bring some answers. That lawsuit is set to go to trial in March 2025.

Coroner’s practice has created uncertainty before

Forensic pathologists say this isn’t the only example of BCCS’s previous practice on drowning deaths leading to stress for a family member.

Milroy and Butt gave expert testimony in a 2020 civil court case that involved an accidental death insurance claim. The decision rested on determining whether the widow of a man who had died after falling out of a boat near Clearwater, B.C., in 2015 should receive an accidental death insurance claim.

After hearing evidence from Butt, who testified for the plaintiff, and Milroy, who testified for the insurance company, the judge ruled in favour of Scotia Life Insurance Co., accepting the evidence that Timothy Downey had died because of a heart attack — a natural cause of death — and not because he had accidentally drowned.

An autopsy wasn’t done for Downey’s death, which happened when he was in a boat on Moose Lake with his 80-year-old mother. Downey, 56, clutched his chest, complained he couldn’t breathe, then collapsed against the side of the boat, causing it to capsize. His mother was able to swim to shore, but Downey never resurfaced.

Butt testified that the coroner should not have listed Downey’s death as “myocardial infarction” based on an external examination alone. He said the fact that Downey had spoken to his mother and then kicked off his boots after he entered the water showed he had “retained consciousness and logical thinking” in the moments before he drowned.

Milroy testified that all the evidence, including Downey’s previous medical history, pointed to him having had a heart attack. Milroy’s opinion was that Downey “either drowned in association with his underlying heart condition, or he died or was going to die as a result of the cardiac event, regardless of the drowning.”

Milroy said the case is an example of where an autopsy could have helped establish the facts.

“There was an issue over what was the true cause and what was the true manner of death in that case,” he told The Tyee. “And obviously, it’s easier to resolve if you’ve done a post-mortem examination.”

Butt has been pushing for wholesale changes to the BC Coroners Service for 30 years. He’d prefer to see B.C. adopt a medical examiner system, similar to what is in place in Alberta, Manitoba and Nova Scotia.

Dr. Matthew Orde, a forensic pathologist who has also been critical of BCCS’s low autopsy rate, says a non-medical coroner system can work — “but only if a team approach is adopted, crucially with trained forensic pathologists having a say in how cases are handled, including the decision whether or not to perform an autopsy,” he wrote to The Tyee in an email.

As B.C. searches for a new chief coroner, the province’s minister of public safety, Mike Farnworth, has been asked repeatedly if the service plans to hire a medical doctor as chief coroner.

Farnworth has said his ministry won’t be involved in that hiring decision. He’s emphasized it will be a merit-based process left to the civil service.

He’s also defended the service’s low autopsy rate for suspected drug overdoses but hasn’t provided information about why he accepts the practice of using toxicology results rather than autopsies.

“The coroner is independent and they are professional, and they base their decisions on their professional expertise,” Farnworth told The Tyee. “It’s not a political decision.”

A family’s heartache

For Debbie Hennig, memories of her beautiful, adventurous younger sister are never far away.

And neither is her pain about how the investigation into her death was handled. Hennig feels the justice system has completely failed her family and Arlene, and said she continues to be revictimized by the lack of accountability and truth.

Hennig says it’s also been painful to witness her mother, Jean Hennig, and sister Wendy Judd experience “unbearable heartbreak.”

Hennig is calling for an inquiry into how the case was handled.

“We were inseparable,” Hennig said of her relationship with Arlene. “She was a free spirit with a quest for knowledge, a passion for adventure and big dreams that were taken from her far too soon.”

Arlene’s death — and the questions surrounding it — haunt her still. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: